A New Gospel for Gay Sinners

Episode 2

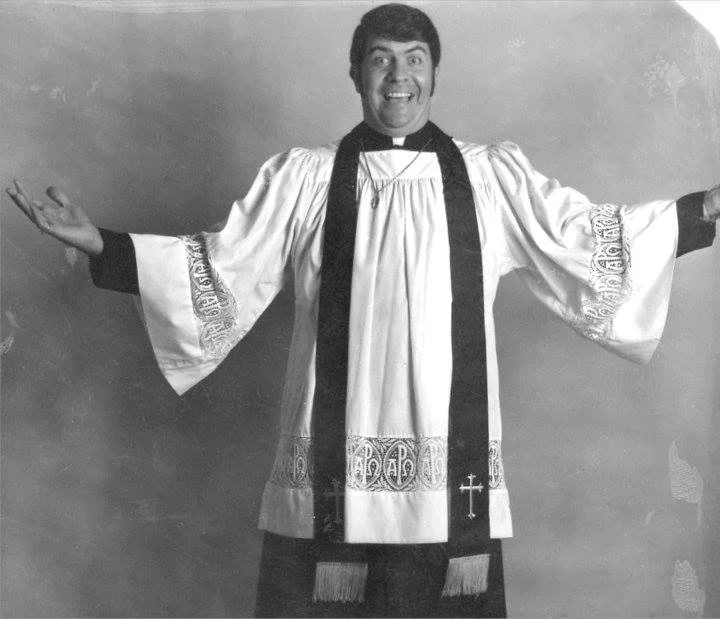

Jackson’s, site of MCC San Francisco’s first gatherings. Photograph by Henry Leleu. Courtesy of GLBT HIstorical Society.

In the 1960s and 70s, the separation between God and gays was not as vast as it appeared. Rev. Troy Perry started the first Metropolitan Community Church in his Los Angeles living room. Howard Wells, tired of flying to LA every week, started the second one in a San Francisco gay bar. And the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco was there for Coni Staff as she navigated spirituality, coming out, and her increasingly conservative family. When her friend Fred got sick, Coni tried to be there for him. Church helped.

Notes:

On Christianity and homosexualtiy in the 20th century United States – and the founding of the Metropolitan Community Church

Rev. Troy Perry, The Lord is my Shepherd and He Knows I’m Gay

Rev. Nancy Wilson, I Love to Tell the Story

Dr. Heather White, Reforming Sodom: Protestants and the Rise of Gay Rights

On San Francisco’s Queer History and the Rise of the Castro

Nan Alamilla Boyd, Wide Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965.

Amin Ghaziani, There Goes the Gayborhood?

Christina B. Hanhardt, Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and the Politics of Violence

Randy Shilts, The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk.

On the early days of AIDS in the United States

The first published reports of what would come to be known as AIDS were “Pneumocystis Pneumonia – Los Angeles.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (Centers for Disease Control), June 5, 1981 and Lawrence K. Altman. “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” New York Times, July 3, 1981.

A classic, but problematic account is Randy Shilts’ And the Band Played On.

A critique of the notion of a “Patient Zero” in the emergence of AIDS is Richard McKay’s Patient Zero and the Making of the AIDS Epidemic.

Larry Kramer’s 1983 article “1112 and Counting” galvanized gay men into action about AIDS.

Hear the full audio from Rev. Troy Perry’s last sermon as the minister at the Mother Church in Los Angeles in 1972 here. He left the congregation in order to lead the rapidly growing denomination.

MUSIC:

“This is the Day” is by Leon C. Roberts. The text is from Psalm 118.

“When We All Get to Heaven,” was written in 1898 by Elizabeth Hewitt.

“Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” was written in 1887 by E. A Hoffman and A. Showalter.

“Blow Ye the Trumpet” was composed by Kirke Mechem for the opera John Brown.

“If Anybody Asks You Who I Am” is a traditional African American Spiritual.

THANKS:

Special thanks to

Scott Bloom and Trogoidia Pictures for the use of clips from the film Call Me Troy.

The Center for LGBTQ and Gender Studies at the Pacific School of Religion and the Graduate Theological Union for the use of an archival recording of Troy Perry’s last sermon as the minister at MCC Los Angeles.

Roy Birchard for hours of conversation about the founding of MCC, MCC San Francisco, and MCC New York.

Kirke Machem for use of his beautiful composition, “Blow Ye, the Trumpet,” from the opera, John Brown.

Resources:

The Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco – the congregation’s current website.

Metropolitan Community Churches – the denomination of which MCC San Francisco is a part.

San Francisco AIDS Foundation – a place to seek information about HIV.

POZ Magazine – a place to learn everything else about HIV (information included).

Save AIDS Research – their recent, epic 24 hours to Save Research conference with all the latest HIV research is available on YouTube through this site.

LGBTQ Religious Archives Network – the place to get lost in LGBTQ+ religious history.

Transcript

Transcript Episode 02 – A New Gospel for Gay Sinners

NOTE: This audio documentary podcast was produced and designed to be heard. If you are able, do listen to the audio, which includes emotions and sounds not on the page. Transcripts may contain errors. Check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Coni Staff: Now, I can tell you about that first service. Would you like me to?

Lynne Gerber: That's Coni Staff telling me about the first time she visited the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco.

Coni Staff: Okay. That first service was really wonderful. we walked in, we looked around, and we saw men. there were a few women, four, maybe So Diane and I almost walked out because while it was very welcoming, it was a sea of men. That's how I've always described it. It was a sea of men.

Lynne Gerber: Coni and Diane – who was Coni’s partner at the time – first went to MCC in 1980. Coni was in her 20s and exploring queer spirituality.

Coni Staff: We didn't walk out though. We sat in the back and we navigated the service as best we could because it was quite different service than we'd ever been to.

Lynne Gerber: She had gone to church a lot in her life. But not to a church like this.

Coni Staff: When it came time for communion, which in typical fashion for MCCs, people walked up and there were, Four or five different stations. it was not a situation where you took some bread or a cracker and you dipped it and then, a short phrase was said to you and you go back to your seat. No, people were. praying with each other up there and touching each other. we did not have the courage to go up and do that, that service, but we did watch and we watched how people were relating.

Lynne Gerber: Going to any church can be a real challenge. It can be hard to sit in those spaces and try to believe that everything being said is true. And to imagine doing all the things you’re supposed to do if you believe. Because sometimes the things being said make no sense. Sometimes they confuse, hurt, or even wound. Many queer folks in the 80s, like many queer folks today, know that wounding, know it intimately. And for good reason would never enter a church again. But for others, like Coni, there's a question or a need or a longing that draws them to religious community. And makes them curious about the possibility of a gay church.

Coni Staff: Now what happened after the service, we Tried to duck out, as folks often do But lo and behold, we hear, This voice from down by the church yelling, wait, wait, don't go yet. Wait.

Lynne Gerber: In this episode we're exploring why a queer person -- why Coni and others -- might go to a gay church in the first place, why they might go back, and why they might stay, even -- or especially -- in a crisis.

This is When We All Get to Heaven. Episode Two: A New Gospel for Gay Sinners.

I’m Lynne Gerber.

Lynne Gerber: Before we tell you more about Coni and what she found at MCC, we want to tell you about how MCC started, and the movement behind it.

Troy Perry: If you love the Lord tonight, would you say Amen? Amen!

Lynne Gerber: That's Troy Perry. He started what became a new denomination -- the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches. As you might have guessed, he grew up in the south.

Troy Perry: As a child, there was something I used to love playing more than anything else in the world. And of course, you probably guessed it already, and that was church. I love church.

Lynne Gerber: Troy grew up in very conservative churches. One part of his family was Baptist, and the other was Pentecostal. In the world he grew up in, that was basically a conservative mixed marriage. And he had this aunt, who had been, in Troy's words,"that traditional lady of pleasure that every small town in the south had." This aunt got saved and then became a preacher. He talked about her in Call Me Troy, a documentary about his life.

Troy Perry: Aunt Lizzie Smithy, she handled snakes, she handled fire, she handled light bulbs, you name it, and she would always quote to me from the book of mark and say, Troy Jr., I believe with all my heart, she said that you called the ministry, but she prophesied over me and said, but I want to tell you now, it won't be in the church of God, the church you're in. I thought she was nutty because I dearly loved the church that I was in.

Lynne Gerber: Troy was a promising young Pentecostal preacher. At 19 he married a preacher's daughter who was also a church pianist. They had two kids and he soon had his own pulpit. He also had a deep pull to men that confused him.

Troy Perry: Pentecostal churches didn't preach about sex, only in the most general sense. But they would have never used the word homosexual from their pulpit back then. And you've got to remember too that I come from a generation where people, uh, viewed homosexuality not as a separate act, uh, but as a heterosexual doing something bad. You know, queer was different. That was a person, that was a sissy. And I knew I wasn't a sissy. Whatever else I may have been, I wasn't a sissy. And that's the way I viewed it. And so, that was the way you justified it in your head. And, yes, I've sinned, but because we Pentecostals believe God can forgive any sin, all I had to do was pray and God would forgive it until the next time I did it. And then I'd pray again and God would forgive me and I'd do it again. So that's how I handled it.

Lynne Gerber: Troy served as pastor in two pentecostal churches. Both times his homosexuality was revealed. And both times he was told to leave. The first time he tried to repent, to double down on heterosexuality and prove his faithfulness. By the second time he was done. He wasn't sure what to do with God, but he was sure he was gay. So he left his wife and family, moved to Los Angeles and started to live that way.

Lynne Gerber: He took some years away from any church. And lived the kind of repression gay people in Los Angeles were living through in the late 1960s. He got caught up in police raids, felt the fear his friends and lovers felt, and started to think the problem wasn't God as much as it was the rest of society. And that maybe God could bring some healing and some courage to people drenched in the shame created by repression.

Lynne Gerber: So he decided to start a church in his living room.

Troy Perry: October the 6th, 1968, I preached a sermon and I entitled it, Be True to You.

Heather White: 1968 is a really interesting moment, right? Because it's before Stonewall. So much of what people think of as the gay rights movement didn't exist. even using the word gay, was not a term that was being used as a movement term. The term in that moment was homophile, which, nobody knows that word now.

Lynne Gerber: That's Dr. Heather White. She's a historian of queer religious life, American Protestantism, and how the two overlapped in the years around Stonewall. Those were the 1969 riots that started when the police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York. It’s widely considered the start of the contemporary gay rights movement. Troy, MCC, and that first Sunday service in his living room were part of the groundswell that led to Stonewall.

Troy Perry: And the spirit of the Lord was there. We felt him. We were all afraid. I really didn't know what to expect. And I remember that I kept watching out of the kitchen.

Lynne Gerber: Till finally, a friend told him to quit watching the door…

Troy Perry: …that a watch pot never boils. Nobody was going to come if I didn't quit looking. But 12 people came and we worshiped and I announced in my sermon that day that we were organizing a church to serve the spiritual and social needs of the homophile community of greater Los Angeles. And it was going to be not a church just for homosexuals, but a church for anybody who wanted to come.

Lynne Gerber: MCC was founded to help gays and lesbians heal their personal relationships with God.

Heather White: Troy Perry's book was titled, The Lord is My Shepherd and He Knows I'm Gay. And that title alone is amazing because It takes the idea that God knows your innermost heart, and flips it to say, yeah, he knows. and he's your shepherd and God accepts you for who you are.

Lynne Gerber: But you couldn't start a gay church in the late 60s without it being a public statement. The mere fact of a church service for queer people where they could be out and not have to repent was saying something. And a church was a space with real social and political possibilities. A space that was different from, say, a bar or a cruising spot or a house party.

Heather White: the Metropolitan Community Church came onto the scene in a moment when everyday sort of movement public visibility was hard to come by. And it was interesting that a church, actually provided a public space for social gathering among gays and lesbians and trans people

Lynne Gerber: MCC started doing things, simple things, that gave gays and lesbians new, different ways to be public about their sexuality. This is Troy talking about checking with the police before MCC held one of the first gay dances in LA.

Troy Perry: he said, I only have one question. Are there going to be any drag queens there? And I said, yes sir, there's certainly going to be some. He said, well just keep them off the streets and everything will be alright. And you know something, we held our dance and nothing happened. Amen.

Lynne Gerber: Doing new, scary things, and having nothing happen, led to the sense that change was possible. A sense that was starting to grow as the gay and lesbian rights movements started to take off after the Stonewall riots. And as Troy started to become an activist.

Troy Perry: I came out of the closet as far as gay liberation was concerned because I said then and there, it's time for us to stand up and take our rightful place in this society too.

Lynne Gerber: In 1970, on the first anniversary of Stonewall, Troy and other gay leaders organized a march in Los Angeles that turned the memory of that local New York riot into the occasion for a national gay rights protest.

Troy Perry: We had our first Christopher Street West parade. You know that story. I was arrested.

Lynne Gerber: Christopher Street West, named after the street The Stonewall Inn is on, is a big part of why we remember Stonewall at all. It was one of the first Pride parades.

Heather White: Because Troy Perry was so visually striking, tall, dark haired, white man with a clerical collar, and that giant cross, if you needed a figurehead, he worked. And so a lot of the media coverage of the first annual commemoration, it was called the Christopher Street Liberation Day, focused on Troy Perry,

Troy Perry: I didn't go there to get arrested. But I was. I really didn't think they would arrest me. The more I sat on that corner and the more they came along. The more I convinced myself they're not going to do anything, they're going to let it slide, but finally I was arrested with two sisters, we were taken to jail, we spent the night, we went to the federal building, we fasted together because we knew that we were right.

Lynne Gerber: Troy's activism grew with the gay rights movement all through the 70s. A lot of the opposition to gay rights came in the form of religious arguments. There are many reasons why religious people were opposed to gay rights, reasons that had to do with beliefs, practices and the interpretation of sacred texts. And some people just used religious language to frame their opposition to gay rights because they knew it was powerful. Either way, as a religious leader Troy spoke back to them on their own terms.

Commentator: This is the worst sin in the Bible. What is this? God's got somebody that's gonna tell you to deal with the truth.

Troy Perry: What is the worst sin in the Bible?

Commentator: Oh yeah, oh yeah, yeah, yeah. You read the verse in Scripture. You read the Bible.

Troy Perry: I have read the Bible. I've read Romans 1, 26 through 28, 1 Corinthians 6, 9, 1 Timothy 1, 9 through 10. Listen, it was destroyed because God couldn't find ten righteous people in a period. That's what the Scriptures say. Nothing to do with homosexuality.

Commentator: Oh yeah, homosex – homosexuality is the worst, worst sin in the Bible.

Lynne Gerber: Religion and gay rights were being set up as inevitable opponents. The loudest voices in religion seemed to be against gay rights. And some of the loudest voices in gay liberation seemed to be anti-religion. But Troy wanted to bring gay and God together.

Heather White: the MCC was really spearheading a kind of activism that brought public attention to homosexuality in general and to gay rights as an idea. But of course he's circulating this in the folksy sort of idiom of Southern Pentecostal Christianity. And in places like New York the gay press didn't so much renounce Perry as just sort of mock him. Just found him kind of embarrassing. the sort of country bumpkin gay guy who's coming into town with his gay Jesus. And that wasn't cool.

Lynne Gerber: But Troy Perry didn't care as much about being cool as he cared about being true to God by being true to himself. And about making a space for gays and lesbians to do the same thing. It's a lesson he had to learn and re-learn himself, over and over. Like when he was invited to preach before a group of Protestant church leaders.

Troy Perry: The National Council of Churches a few years ago came to this city. And they invited yours truly to preach. They wanted to see what Troy Perry sounded like and see what MCC was like. And, you know, I thought it, and I'll have to be honest, you know. I sit around and I think, dear God, why do they want me to preach? Number one, my Lord, what if I mispronounce a word in front of all these bishops, in front of the presidencies, denominations, Oh my goodness, and I thought about that and worried about that, and my friends talked to me about it, And said, listen, this is when you're your best. You just be you. Let them meet MCC just the way we are. And I remember that my next big thing was, dear God, shall I wear my earring or not? That was just, you know, mind boggling for me. I worried about that. And then I thought, yes, wear your earring. Just be yourself.

Lynne Gerber: That was the heart of Troy's message -- to be yourself. Because God made you, and God knows full well how God made you, and God loves you that way. His church made a space for folks to practice living that message. And people were drawn there. But not everyone who found MCC life-giving lived in LA. Some folks wanted to take Troy's message and make that kind of church in other places. People like Howard Wells, who moved to San Francisco in 1970 after being honorably discharged from the Navy.

Howard Wells: And I had just come out, so San Francisco was definitely the place to be.

Lynne Gerber: Howard grew up in Texas and was nominally Southern Baptist. But he wasn't especially religious. Until he heard Troy Perry.

Howard Wells: And I was flying down to LA every week to go to church. That was the only MCC there was. And that was rather expensive, even back then. And I thought, well, maybe on the weeks that my paycheck just doesn't go far enough, maybe we can have sort of like a little prayer meeting with one or two people in the Bay Area, who occasionally went down to LA for church, and so I invited the people I knew to come to my apartment and have a little prayer meeting, I'd never been to a prayer meeting in my life, to be quite frank with you. And, something very special happened there. within a month we decided that, God was demanding a scandalous, outrageous thing of us, and that was to start a church in San Francisco. Everybody thought it couldn't be done, that that only happens in Hollywood.

Lynne Gerber: San Francisco was long known as a wide-open town, a place of danger, experimentation, excitement, possibility. From its Gold Rush boom days it attracted people living outside of conventional morality. And after World War II it started attracting more and more queer folks. By the 70s it was known for its large gay community. And for gay bars actually owned and run by gay people as opposed to the many gay bars run by organized crime in the period.

Howard Wells: We had rented out a room above a, a bar named, called Jackson's Bar on, Powell and Bay Street. And they called it the penthouse, and we called it the upper room.

Lynne Gerber: Jackson’s Bar became MCC San Francisco’s first home. But as the months went on it couldn't hold all the people curious about this church and the fledgling movement it was a part of. So in 1970 they planned a big event, a spiritual renewal that would introduce MCC’s founder, Troy Perry, to the city. They took a big risk and rented out California Hall, a venue that seated 1000 people.

Howard Wells: And, that night when we opened the doors, people were waiting to come in. We filled up the bottom floor and they started going into the, to the, To the balcony area. Hundreds upon hundreds. It was just mind boggling. We couldn't believe what was happening. I was so proud of this group. I just All night I'd lay in bed and just giggle.

Lynne Gerber: After that Spiritual Renewal, MCC San Francisco took off.

Coni Staff: I moved here Five or six years after Stonewall

Lynne Gerber: Coni and her partner moved from the Midwest to San Francisco to be professional coaches and athletes -- and lesbians. Like a lot of queer folks, they were drawn to a far away city to experiment with a new way of being in the world, one that wasn't possible in the places they were from.

Coni Staff: the Castro was not the place yet, It was Polk street. That was the place in San Francisco to go and find community. and still it was a sea of men, you didn't so much see women, but I can remember, my partner and I, when we first moved out here. “Let's go drive down Polk Street,” so we would, we'd drive down Polk Street and then we would see, men holding hands or standing on the street cross dressed or, Oh, did you see that? Oh, did you see that? I mean, this was big revelation. This was out in public. This was not done back where we came from.

Lynne Gerber: Coni grew up in Illinois in the 50s and 60s in a family of teachers and athletes. She loved God but was confused about church.

Coni Staff: Early in my life, of course, from time to time, there were sermons that were given on morality. And as I began, being older, I remember my feelings sitting there in the pew. Because the sense of it was that people who were homosexual were abiding against God and were sinning. And we're most likely leading others into sin and were to repent.

Lynne Gerber: She could almost take what the church said about her in stride. But not what the church said about God.

Coni Staff: it was hurtful to hear that I was disappointing God. And I did not fundamentally believe that, but it was still hurtful to hear it from a pulpit.

Lynne Gerber: Coni moved to San Francisco to come out. Which meant different things to queer folks in this period. For some, it was a matter of personal freedom. Hiding their sexuality made their worlds too small and they wanted more space. For some, it was political. Leaders like Harvey Milk told gays and lesbians that the only way to make more space was to be out about who they were. Gay people needed to be seen and known for society to change. And for people like Coni, coming out had a spiritual dimension that combined both. Coni was out in her San Francisco world but she struggled with her family back home. Not coming out to her family caused her deep pain. Turns out, coming out did too.

Coni Staff: I did go back in 1980 and came out to my parents in person. It did not, it did not go how I had hoped. And our relationship changed quite a bit. I saw them go into right wing Christianity. I had been raised in the church. I had been raised in the Methodist church. We went to church every single Sunday. Very important for our family. Once I went to college, I had stopped going because I'd heard enough sermons, uh, at that time about who the ministers felt that I was.

Lynne Gerber: Religion was the source of struggles for many gays and lesbians navigating coming out. Some were happy enough to walk away from the whole thing. But for others, there was something about religion, or what they believed religion meant, that was core to the whole question of sexuality and coming out. Faith, sexuality, and identity were all interconnected for them, and truth-telling was their shared core. Those folks wouldn’t just walk away from religion. But the movement didn't always have resources for them.

Coni Staff: I had already gone down to one of the several gay bookstores in the city. And I had rummaged around. It wasn't a very big bookstore. The proprietor saw me, and of course, I was the only one in there, and he asked me what it was I was searching for, and I said, I'm looking for anything that has to do with Christianity and homosexuality. And he looked at me, and he smiled, and then he kind of chuckled. Which wasn't a good sign to me. And he said, well, good luck with that.

Lynne Gerber: But there was this church -- this gay church.

Coni Staff: actually the very first reason why I got connected with MCC was that Diane had the idea, because I was experiencing a lot of pain about my family, that we should go down to MCC San Francisco to speak with someone, and maybe they had some answers how I could respond to my family or that kind of thing.

Lynne Gerber: So Diane and Coni went there and talked to someone. An MCC minister. They talked about the Bible, about her family, and about how coming out was making her more spiritual at the same time it was making her family more religiously conservative.

Coni Staff: And at the end, he said, why don't you think about coming here to a service? And Diane and I looked at one another and we, We kind of shrugged our shoulders. It's like that hadn't even occurred to us. So that's actually how we got to MCC San Francisco.

Lynne Gerber: When Coni and Diane first went to MCC, in 1980, it had just moved to the Castro. After that spiritual renewal in 1970, the one that left Howard Wells so happy he was giggling, the church moved to different places around the city. As it moved it gained some visibility and some status. Its second minister was an integral part of the gay political infrastructure of the city. And its visibility drew supporters, detractors. And violence.

Coni Staff: the biggest memory I have of the space was this very prominent wooden cross. that was hanging at the front of the sanctuary. I learned later that that cross was made out of embers, saved from when the church was put on fire by an anti-gay person. earlier in that church's history.

Lynne Gerber: We learned from another congregant that the cross hadn't actually been in the fire, which occurred in 1973. But it became a powerful story in the church because the fire was a turning point. The arson was condemned not only by gay leaders but by straight leaders too. According to Troy Perry, Dianne Feinstein, who was a city supervisor at the time, made the first donation to the church's re-building fund.

Lynne Gerber: A lot of other things happened in the 70s in San Francisco, gay things and religion things which shaped MCC and how it grew. Harvey Milk was elected as one of the country's first out elected officials in 1977. And in 1978, he was assassinated. A religious group of progressive Christians, known as Peoples Temple, made their home in San Francisco. Until their leader Jim Jones moved them to Guyana where hundreds died in a night of collective suicide that Jones provoked. That also happened in 1978. Many people in San Francisco knew someone who had died in Jonestown and spiritual communities were looked at with newfound suspicion. And the Castro had become the city's -- and the country's -- most visible gay neighborhood. In 1979 MCC bought a building there on a quiet residential street three blocks from where Harvey Milk had his camera store. And 150 Eureka Street became one of the first public spaces owned by an LGBTQ organization in San Francisco.

Coni Staff: back then, all kinds of folks came to that church. People who were, Searching for answers. People who had been supremely hurt by their church. People who had been tossed out of their families for good. People who were struggling with drugs. People who were struggling with alcohol. People who were struggling with sex addiction, people who were struggling to keep it together mentally, people who sometimes acted out. people who were extraordinarily functional, people who were in the middle with functionality, people who were not functional at all. So in this grand mix of folks, if I placed myself back in Jesus’s time, this is what I expect, Jesus might have been talking about, might have been dealing with.

Lynne Gerber: Coni was finding something different than she might have found at a gay-friendly church in a more traditional denomination, like the Methodist church she grew up in. Making a church by and for gay people allowed them to reach out to a wider range of people. It allowed gay people to participate in Christian community on their own terms, as makers of religious spaces and enactors of Christian rites. As providers of religious gifts, not recipients of religious pity. By being out gay believers at an MCC, they didn't have to fight for religious space in the churches they came from. They could make their own.

Coni Staff: So it really was a no brainer that we were coming back, you see, because we had found, god had found us again, right? And we were open to it. But who wouldn't be open to that? that church saved lives by simply being a reality, a place where people could walk into even if it was one Sunday of their life and that was it. That might be the reason they stayed alive. And this was before AIDS.

Lynne Gerber: In the 1970s, gay men and lesbians didn't necessarily see themselves as partners in a social movement. They had different communities, different cultures, and sometimes were opposed to each other. And when gay rights groups started bringing them together, there were some issues to deal with.

Coni Staff: as women, we had a different orientation to partnering than we were witnessing with our brothers in the church. Not all of them, but some of them. And we weren't understanding their orientation to coming together and how making love and sex and commitment or non commitment worked in that. We just knew it didn't really seem to work for us. And that's not really what we wanted to do. And the bath houses now, not all women felt that way, but a lot of us did. and the bath houses were a topic of like, we don't get it.

Lynne Gerber: And then this disease starts erupting. The first reports of AIDS appeared in the media in the summer of 1981. But in San Francisco rumors were already starting to spread.

Coni Staff: So now, there are a few guys who are a little sick and they don't seem to be getting better out in the community, there were more people getting sick and some of them were beginning to die. And nobody knew what was going on. The disease did not have a name because the doctors didn't even know what it was. There were no treatments for it. There was great fear as the weeks and months went on because the medical establishment didn't have any answers. The bathhouses were talked about even more because could this be a way it was spreading? There was great resistance in the men's community to closing the bath houses because this was part of their lifestyle, the way they lived. Some of them lived. So we were all in a great flux.

Lynne Gerber: AIDS started as something that felt pretty far away, even to queer people. Early on, a person could convince themself they were safe because they didn't party, or because they weren't a leather person, or because they were a leather person, or because they were monogamous, or they never, ever, ever took drugs. Basically because they were somehow good and the people who got it were somehow bad. There's a fantasy of safety in that. But AIDS didn't work that way. And for Coni it got pretty close pretty early, forcing her to put questions of judgement aside and dive right into the catastrophe. It started with her friend Fred.

Coni Staff: Fred Reeves was the first person I knew very well who got sick. He had missed a number of services and we started asking about him

Lynne Gerber: Coni knew Fred from church. They were in something called a Lenten Living Room group together. Lent is the 40 days before Easter when many Christians enter a period of reflection, give up things they love and seek greater spiritual understanding. At MCC people joined these small groups of 8 or so people who met at folks' homes -- their living rooms, theoretically -- to consider their spiritual lives together.

Coni Staff: You got pretty close, and part of that was praying together and all the other things you talked about, and people brought issues that they were seriously dealing with to that group. And we all became a family of sorts.

Lynne Gerber: So when Fred started to change, Coni noticed.

Coni Staff: He was clearly losing weight. and he just didn't have that energy. And he had a certain look in his eyes that I'm not sure I can describe. It was – the twinkle was there less. The brilliant shining out had been dulled some.

Lynne Gerber: People didn't know how to respond to AIDS, didn't know how to stay safe, didn't know how to be with people who were sick.

Coni Staff: Sometimes we would talk to each other a little bit, like, what do you think? What is this? How is Fred doing? How is so and so doing? I mean, are they worse? Did you see this, the spot on his arm? Why do you think that is? There seem to be more spots on him. They don't think we can catch it from touching.

Lynne Gerber: People couldn't help being curious. Or being scared. But they also couldn't help loving their friends. And wanting to help,

Coni Staff: Fred was getting sicker and sicker, and he came to church rarely. I remember the last time he was there, he, he was having trouble sitting up. He was just kind of slumped in the service. He had lost a lot of weight. He didn't look like himself at all. His face was gaunt. His color was really yellow. And very soon after that, within a week or two, he was no longer able to leave the house. Now he had care, friends, caretakers, helping him along the way. And again, we still didn't know how it was transmitted or whether any of us were in danger or not. So they were taking turns being at his house, helping him do certain household things. And then he got worse to the point where he was having trouble leaving the bed. And so a call was put out at church that his caretakers really needed more assistance. They were getting tired. Of course they were. And more hours were going to have to be covered. Nobody else was going to show up, right?

Lynne Gerber: The physical needs of people with AIDS brought folks to this very sharp edge of love and fear.

Coni Staff: This was the first time that I had done that kind of assistance in someone's home. That was a really hard afternoon. I have to say, that was a really hard afternoon.

Lynne Gerber: And for people like Coni, religion provided some of what they needed to acknowledge the fear but move toward the love.

Coni Staff: I got there and it was just Fred and I. Now he was sleeping in his room but I was afraid. It wasn't so much that I was afraid that something would happen to me in that moment, although that was there. I was afraid I might not be able to do some of the things that he needed from me. That I wouldn't know how to do them. Or I might not be strong enough to help him, or… There were fears coming from several angles. And I sat there in his room for a little while at his bedside. And I finally got up and I went out into the living room. You know his bathroom was filled with medications, they weren't working, but it was filled with medications, and there were towels and washcloths and glasses that he had used and forks. I mean, you know. I went out into the living room and I just sat down there and I started crying because I wanted to be able to be there for him a hundred percent. And I didn't know how to be, and I was afraid. And so I just prayed. I just prayed, God, please, I could cry right now remembering that day. Those moments, please, God, please, please help me. Please show me, please. I want to be here. Please, please take this fear away from me. Let me serve him. Please. I love him. He's dying. I think he's dying. Please, God.

Coni Staff: And after half an hour, maybe it was longer, I took a deep breath and I walked back into his bedroom and I sat down. And I just started reading to him, talking with him. He couldn't say a lot. He was sick. He was really sick.

Coni Staff: And we did all we could and what we did the most was that we showed up. We were there. We didn't have to say anything. We came to know that what was most important was not any certain thing we could say, because there weren't any words to deal with this. It was that we came and we sat there, and if it was in silence, it was in silence. If it was holding Fred's hand or somebody else's hand, it was holding their hand. If they wanted us to pray the Lord's Prayer, which many a guy wanted. Even the guys that were not going to church and would have denounced it prior to AIDS. Many of them wanted the Lord's Prayer said at the end. Whether their mother had come to be with them or whether their mother and father had rejected coming, we came.

Coni Staff: And it was, the men showing up for their brothers, many of whom became sick later too. The men showing up for their partners and there were many, many, many women in the earliest stages of AIDS who showed up for their brothers, because we understood that nobody else was going to be there. Our brothers were getting sick. Their friends, yes, could be there if they were well enough to be there. But we could be there. Their sisters could show up.

Coni Staff: Fred died not long after he was in the hospital, but he died having had a number of visitors from the church he was one of the first to go. He went fairly fast. The first of so many.

Lynne Gerber: When I first learned about MCC I thought I could imagine some of the things they said there. That it's okay to be gay. God loves you. You're not going to hell. You don't have to be ashamed. MCC did and does say all of those things. But for Coni those weren't the most powerful messages.

Coni Staff: even in those first services I attended, it was clearly there that we were much more than God reaching out to people who are hurting. We were in essence, a gift back to the church at large. And that's nothing that many of us had ever considered. And that this is a joyful thing, a thing to celebrate. And we're going to celebrate because we are MCC and we are MCC in San Francisco..

Lynne Gerber: The thing that was most powerful was the possibility that gay Christians had something of value to share. That there was something in bringing together sexuality and religion that could teach the church -- the whole Christian church -- something new about both. That queer people of faith could enact Christianity in a way that everyone could learn from.

Lynne Gerber: AIDS made that possibility more visceral. And as AIDS spread, MCC San Francisco knew it would have to grow and change with it. And that it would have to attend to their community before attending to Christianity at large.

Coni Staff: There were people from the community that were also coming to MCC San Francisco who might have come to a service in the past or might never have, but were wanting memorial services because where else were they going to go? this was a huge impact on the congregation, and we still didn't have a lot of answers, but we knew we needed to respond with our faith.

Lynne Gerber: And they knew they would have their own losses to attend to, losses they knew were coming.

Howard Wells: I want to say also that and reiterate that by having me here today and honoring me with having my name on that plaque outside, is a grace filled act. It's a manifestation for me of the kingdom of God.

Lynne Gerber: That tape we heard of Howard Wells telling the story of founding the church in Jackson's bar – and the tape we’re hearing now – was from a special service in the late-80s. He preached a sermon that Sunday and the church installed a plaque on the outside of the building that named him as its founder. They wanted to honor him while he was still there.

Howard Wells: It confirms my life, that the 17 years I've put in MCC hasn't been a waste.

Lynne Gerber: The recording of it was played two years later at his memorial service.

Howard Wells: I was telling Jim that in many ways, [00:46:00] that plaque could be considered as a, I hate to use the word, a tombstone, but it's a tombstone on something that's living and dynamic. And what a privilege it is to have a mark of Howard Wells on something that's living instead of sitting out in some empty field. And I'm seeing it while I'm here.

Lynne Gerber: Dying and grieving and living and dynamic. All words that described MCC in these years. How to hold all of them at the same time - as the losses mounted, the politics raged, and faith was hard to find -- that was something its leaders were going to have to get even better at.

Next time on When We All Get to Heaven – a gay church becomes an AIDS church.

Dennis Edelman: It was almost like a collective epiphany. We're dying and we're going to live these years positively. We're going to act up. We're going to speak out. We're going to change things. We’re going to defeat Ronald Reagan.

CREDITS

When We all Get To Heaven is a project of Eureka Street Productions and is distributed by Slate. It was co-created and produced by me, Lynne Gerber, Siri Colom and Ariana Nedelman.

When we started this podcast AIDS felt more like history. Now it feels more like current events. If you want to support the important work being done countering the current challenges to AIDS research and treatment, there are links to good groups in the show notes. They’d love your support.

Our story editor is Sayre Quevedo. Our sound designer is David Herman. Our first managing producer was Sarah Ventre. Our current managing producer is Krissy Clark. Tim Dillinger-Curenton is our Consulting Producer. Betsy Towner Levine is our fact checker. And our outreach coordinator is Ariana Martinez.

The music comes largely from MCC San Francisco’s archive and is performed by its members, ministers, and friends. Additional music is by Tasty Morsels.

We had additional story editing support from Arwen Nicks, Allison Behringer, and Krissy Clark. Our interns are Nico Kossakowski, Carrie Hale and Victoria Nascimento.

A lot of other people helped make this project possible, you can find their names on our website. You can also find pictures and links for each episode there at – heavenpodcast.org.

Our project is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, the E. Rhodes and Leona B Carpenter Foundation and some amazing individual donors. It was also made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. You can visit them at www.calhum.org.

Eureka Street Productions has 501c3 status through our fiscal sponsor FJC: A Foundation of Philanthropic Funds

And many thanks to MCC San Francisco, its members, and its clergy past and present – for all of their work and for always supporting ours.