Tired of Dying

Interlude

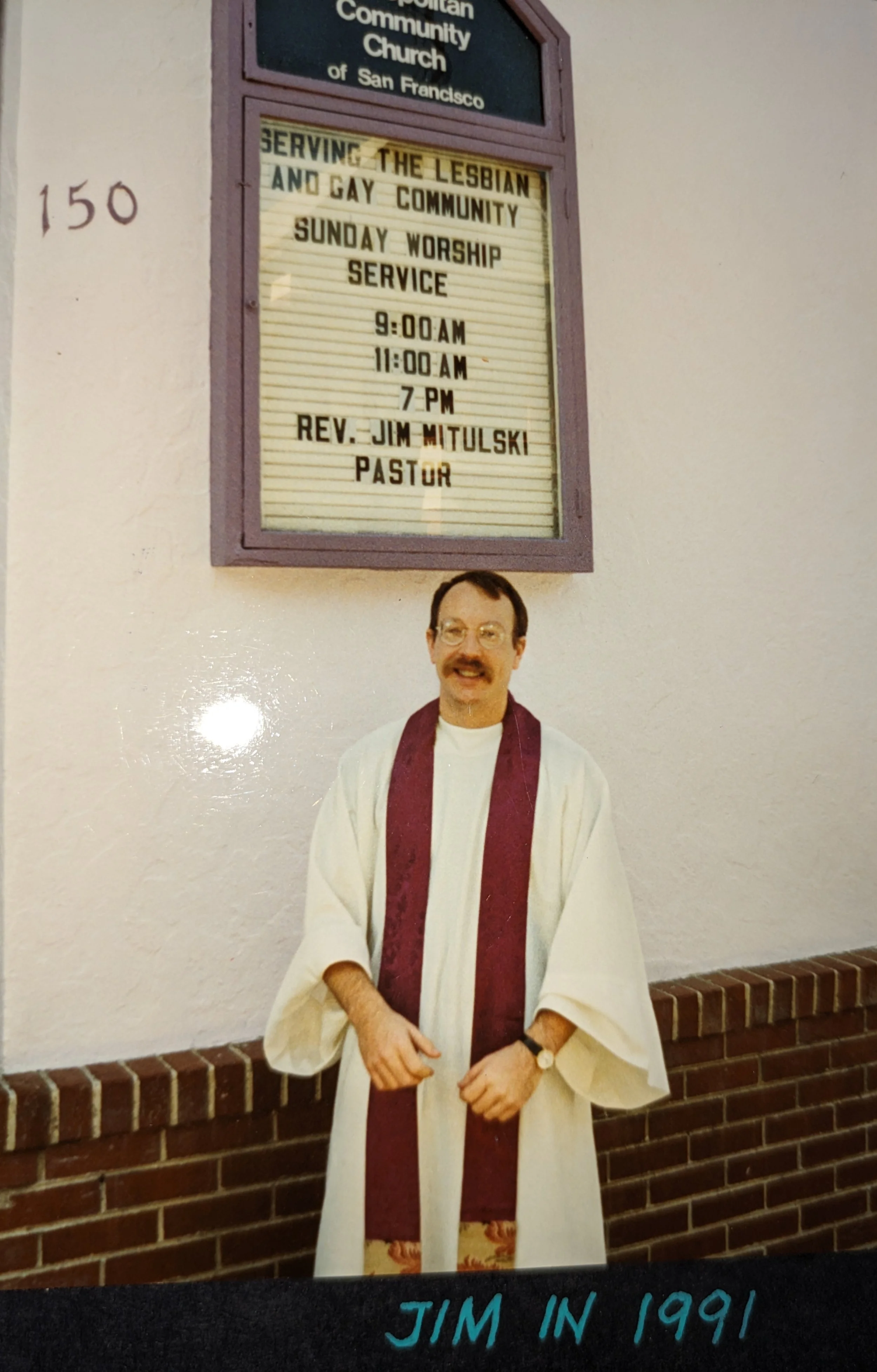

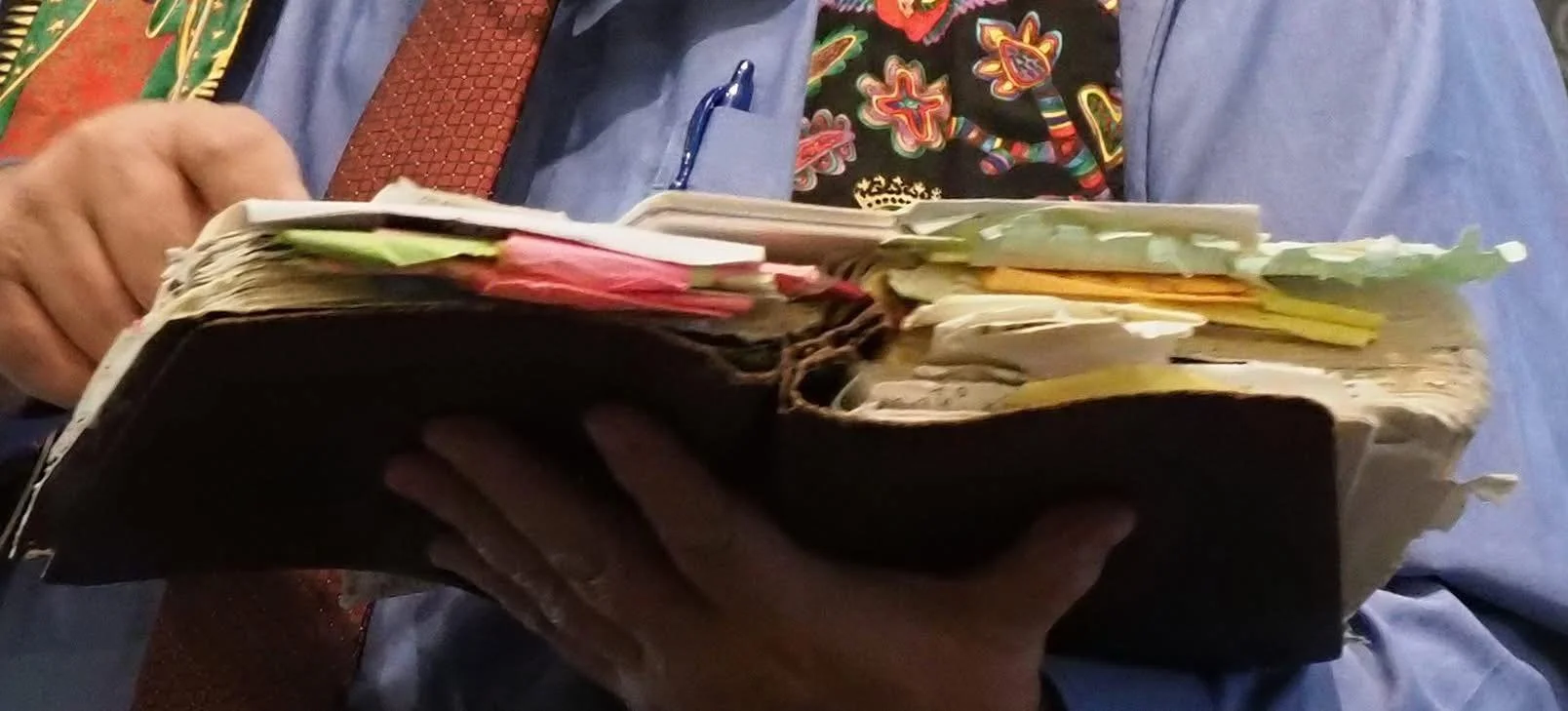

Rev. Jim Mitulski preaching, Bible in hand. Date unknown. Courtesy of Metropolitan Community Church collection, San Francisco Public Library.

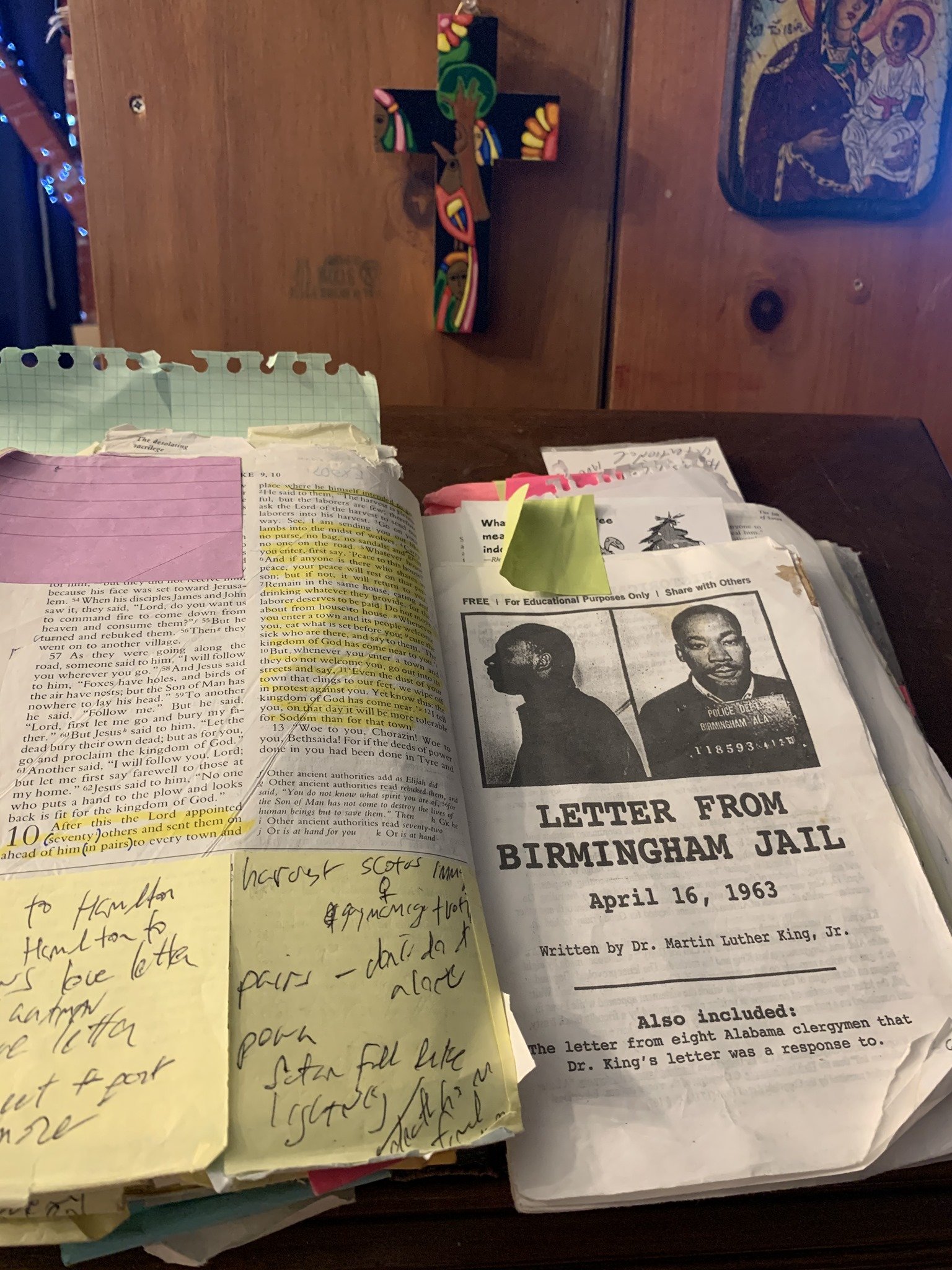

The Sunday after Magic Johnson announced his HIV-status, Jim Mitulski preached a sermon on being tired of people dying. We’re sharing it as an interlude, a pause, and an immersion into one moment in AIDS’ bleak midwinter.

NOTES:

In the sermon Rev. Mitulski refers to ARC. That means AIDS-Related Complex, a diagnostic category meant to indicate an earlier stage of HIV infection than AIDS. It was common in the period to hear references to both AIDS and ARC.

You can see Magic Johnson's press release, announcing his HIV status here.

The biblical passage Rev. Mitulski is preaching on is John 11:1-44.

Music:

“Old Devil Time” is by Pete Seeger. The AIDS verses are by MCC San Francisco congregant Paul Francis.

The music for this episode is from the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco’s archive. It was performed by MCC-SF’s musicians and members with Bob Crocker and Jack Hoggatt-St.John as music directors. Additional music is by Domestic BGM.

THANKS

Great thanks, as always, to the members and clergy of the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco who made this project possible.

Resources:

AIDS Healthcare Foundation – provides medical care and support for people living with HIV/AIDS and preventative care for people at risk for contracting it.

The Magic Johnson Foundation – founded to address HIV/AIDS. Expanded to include education and community engagement.

San Francisco AIDS Foundation – a place to seek information about HIV.

POZ Magazine – a place to learn everything else about HIV (information included).

Save AIDS Research – their recent, epic 24 hours to Save Research conference with all the latest HIV research is available on YouTube through this site.

TRANSCRIPT:

Interlude – Tired of Dying

NOTE: This audio documentary podcast was produced and designed to be heard. If you are able, do listen to the audio, which includes emotions and sounds not on the page. Transcripts may contain errors. Check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Lynne Gerber: This is how Reverend Jim Mitulski prepares to preach a sermon.

Jim Mitulski: So I look at, I read the room. I don't know how to do this, but I've always done this. Since childhood, even. I can feel a room. It's not infallible, but I have my texts. I know I'm going to talk about that passage and I have my notes that I've prepared for what I know all week long. And then I feel it and then I do it. I can't even tell you how, I don't know how I do it, but I do.

Lynne Gerber: The sermon is the part of a worship service that people sometimes dread. The minister gets up in front of the congregation, Bible at the ready, and starts to talk. And talks for a long time. Sometimes a really long time. The listener may be judged. Or shamed. Or confused. Or put to sleep. But, in the hands of a good preacher, it can be the most life-giving part. Because a good sermon helps make sense of what's happening in the world in relation to texts that are deemed sacred and beliefs that are deemed holy. Something especially important when the distance between the world and the holy seems impossible to bridge. And the journey feels never-ending.

Jim Mitulski: And during AIDS, there was a lot of trying to feel what needed to be said. including who had died that week or what was on people's minds or what was happening in the news around AIDS or gay or the world.

Lynne Gerber: A good preacher needs to know their congregation and what it's going through.

Jim Mitulski: Um, but a lot of it was, where's the grief? Where's the grief this week? Collectively, not that everyone was experiencing it, but there often was a collective feel to it. Where's, where's, where are people around this or where's the anger? What do they need? So, that's what, that's what I would feel. I would feel it.

Lynne Gerber: In this interlude, just over halfway through our story, we're going to do something a little different. We're going to play one of Jim's sermons from start to finish. Just like the congregation at MCC San Francisco heard it on a Sunday evening in the fall of 1991, 10-plus years into the AIDS crisis. In 1991 MCC San Francisco had lost a lot of people already and were facing more losses ahead. And no one knew if or when that might ever change. So Jim read the room. And he preached a sermon on being tired of people dying.

We hope this will give you a real connection to that moment, to this community and to its struggles. And that it will give you a good word for your own long journeys.

This is When We All Get to Heaven. Episode 7 – An Interlude: Tired of Dying. I’m Lynne Gerber.

Jim Mitulski: I wanted to talk tonight about, and I mentioned it in the last few weeks, and put it in the bulletin so you would know in advance. Um, a feeling that I know I've been having and that others have articulated to me, which is this, I'm tired of people dying, tired of people I love dying. And it started for me, this feeling started forming, I think, I also want to say that if you don't come here regularly, that I tend to do teaching sermons in the morning and feeling sermons at night. This is a feeling sermon. Um, nope, I didn't read this in a book, um, but I think we know about what I'm talking about.

Jim Mitulski: I got a letter from a congregant about a month ago now, I guess, and I got it after a Sunday in church when, uh, there were several people who had died in that previous week, and I was announcing that to the congregation. And so she wrote me this letter, and she'd not been in church for a little while, although she came that Sunday, and she says, Dear Jim, I'm selecting from it, It's been a while since I've been to church. And when I was back last Sunday, I realized I was in a state of denial. Maybe if I don't go, I won't have to hear about people dying. Well, as you know, people do keep dying, and so many fine people they are. Well, I have a choice to go or not. I get to decide if I want to go this moment, or take a drive on Sunday, or just stay home. I think what I'm trying to express is my frustration with life at this moment and in all its unfairness. It is unfair, all of it. And yes, I know how good things rise up from the ashes, and they will. My faith is pretty well grounded in me. You and my Catholic teachers have done a good job. I'm not sure I want to be grouped there. (Laughter) I've been at church now long enough to get to become friends with the men. Before, I didn't know the names that were announced. And now, not only do I know them, I have pictures of them in my albums. October is one hell of a month, isn't it?

Jim Mitulski: The minute I read it, I knew exactly what she was talking about. And I know that we all have, to some extent or another, connected with that feeling. I can't take the thought, the feeling, of one more person that I love leaving.

Jim Mitulski: When, uh, when, uh, It also reminded me, I finally understood why I was so angry about eight weeks ago when two members of our church moved to Washington, D. C. Uh, all they did was move, but I was really mad. And I just realized all of a sudden, I hate saying goodbye right now, whether it's because someone moves, um, or because they die. I just hate it. And maybe you know what I'm talking about. I have a lot of feelings around this and I know that others of you do too. And, and I became aware of the depth of the feelings that we have. The depth of all the things going on around this particular topic.

Jim Mitulski: Um, just this past week also. in the events around Magic Johnson revealing his HIV status. And of course, this community commends him and understands what it means for him to identify in the way that he's identifying, for who he is and what he is. And we appreciate that, probably in ways that other communities don't really get. Um, but, uh, There are a lot of dimensions of it that made me realize how angry and how crazed I am around this right now.

Jim Mitulski: It started for me, I was on an airplane, uh, for nine hours from San Francisco to Los Angeles. And, it's not, it was the Thursday that he announced his, status, And you know, Los Angeles is not worth a nine hour plane ride. Uh, and I was on the plane, and in the way the universe has of arranging these tortures, the person next to me, um, started out by saying, uh, Are you a basketball fan? And, I don't know. I have old, old fashioned homosexual values. I, you know, I looked at him and I thought, No. And then I realized, maybe this is how straight men meet each other. And then he said to me, Well, what do you think about Magic Johnson? And I said, this is the truth. I didn't know who he is, but I can tell you who's sang a lot of disco songs, but as the events around that unfolded and as people's responses, as I heard people on the radio say things like a car radio, of course, cause I was in Los Angeles saying, um, This is the first person I've met with AIDS, or I know that has AIDS. I would just, I would practically drive off the road when they would say that, because I think that they were expressing a truth for them, that's important. Um, that really is true. But I can't imagine where they've been for the last ten years.

Jim Mitulski: And someone that I was talking to in the church in, uh, Hollywood, where I was preaching last Sunday, talked about, uh, talked, I was talking about it with him, and he said that he realizes that he has an AIDS consciousness. And It's like a, a gay consciousness, you know, if you're very gay or lesbian identified and everything, that becomes the lens through which you see things. Now he's at a point, and I think I'm at that point too, where AIDS is actually the lens through which I see things. Almost everything I hear, I, I check it against the fact of that in our lives right now. Whether it's good or not, I don't know, but it's the truth for me. Um, I'm, I have that AIDS consciousness. And when I would hear things like, uh, as I said in the morning worship this morning, Vice President Quayle saying things like, um, well now maybe we can do something so that Magic Johnson never has to experience, um, the full blown AIDS. I, I just went, you've got to be kidding, you know. Um, and when we talked about it in the HIV groups in this past week, they talked, uh, a lot of the guys talked about, um, feeling like they'd been dismissed or discounted for ten years, as if now, all of a sudden, someone worth saving has become apparent. So these are all dimensions of, um, that feeling that I think comes out as, I'm really tired of people dying. I'm scared of people dying. I'm scared of losing one more person that I love.

Jim Mitulski: So I thought about a Bible story. I tried to think of one in which, um, some of these sentiments are reflected. You know, there are many different ways to read the Bible stories. And I read them as they are literary texts. I don't think that their greatest value necessarily is to teach theology or doctrine. I think that they're stories that people wrote about how they were experiencing not only God but each other. And that's the true value of those stories, not the doctrines that sometimes the editors have tried to overlay onto very human interactions. So I want to use a story from the Gospel of John, and the Gospel of John is not a, not a book that I use very much because it's one of those books that was written so long after Jesus died that it has so many layers of theological things in it that I don't think were part of it, the original. It's not that they don't have value, but I think that they were overlays. But see if you can connect in this story from John's Gospel, um, about people, and particularly Jesus is the center of the story, who was really sick of people dying.

Jim Mitulski: From the 11th chapter, some excerpts. There was a man named Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and Martha, her sister. And Lazarus was ill. This was the same Mary, the sister of the sick man Lazarus, who anointed Jesus with ointment and wiped his feet with her hair. The sister sent this message to Jesus. The one that you love, Lazarus, is ill. On receiving the message, Jesus said, This sickness will not end in death, but it is for God's glory. Jesus loved Martha and her sister Lazarus, and yet, when he heard the news that Lazarus was ill, he stayed where he was for two more days.

Jim Mitulski: In those very opening verses of this story, I think we have a picture of a group of people who love each other. Jesus, Mary, Martha, Lazarus, familiar characters in the New Testament, intimate friends of Jesus. And there, we know them from other stories as well, Mary and Martha, and they, uh, send this word to Jesus, This person that you love, your friend, is really sick. And Jesus’s response to hearing this news is not immediately to rush to Lazarus side to see him, to talk to him, or to be there, but it says, he stayed where he was for two more days. There's no doubt in this text that Jesus loved Mary and Martha, and especially Lazarus. But I think that Jesus even was in denial at that point when he said, This sickness isn't really serious. He's not going to die. Perhaps some blessing will come from it. When Jesus heard that Lazarus was sick, it says he stayed in the place for two more days, even though the place where he was, Bethany, where Lazarus was, Bethany, was just a few miles away. It wasn't an airplane ride, um, it wasn't across the state, it wasn't across the country. It was just a few miles away, something he could have walked in a matter of hours.

Jim Mitulski: I think, I love this image of Jesus because he would understand how we might feel if we're afraid to go to the hospital. If we're afraid to not return the call of a friend who's sick. If we're afraid to not go to a memorial service for someone who'd been a very dear friend. Jesus stayed away because I think he was afraid of what it would feel like to go through the death of his friend. And I believe that these feelings of being sick of people dying has nothing to do with our HIV status. Some of us are HIV positive or have ARC or AIDS and feel this feeling. Some of us are not and feel this feeling. But Jesus understood it as well.

Jim Mitulski: So Jesus stayed away, and it says that Lazarus died, it goes on to say in the text that Lazarus died, and Jesus then heard about it, or knew it, and he decided to visit at that point, after Lazarus was dead. And then the scene shifts, To Jesus approaching where Mary and Martha are, and it says, um, On arriving, Jesus found that Lazarus had been dead, had been in the tomb already. Bethany is only about two miles from where they were. And many people from the religious assembly had come to Martha and Mary to comfort them about their brother.

Jim Mitulski: When Martha heard that Jesus was coming, she went to meet him. Mary remains sitting in the house. This is typecasting, I want to interject. You might remember that it's Martha is the one who does all the cooking and cleaning, and Mary is the one, um, who sits and does the learning at Jesus feet. So, there's a little typecasting here. It says, Martha went to see Jesus, but Mary remained in the home. Um, and then, uh, Martha says to Jesus, If you'd been here, my brother wouldn't have died. And that too is a feeling that, um, I wonder if you've ever felt yourself, if you'd been here, if I'd been here, if only I'd been there, if only I'd done the right thing, whatever that right thing is, that impossible thing, that thing which I bargained to do, uh, bargain with God at times it feels like, then perhaps this one would not have died, my friend, my loved one.

Jim Mitulski: Jesus and Martha. Uh, converse with one another, almost argue with one another. Jesus says to console her, well, don't you believe that you will, that your brother will rise again, that you'll be reunited with him? Because the sect of Judaism that, uh, Jesus and Mary and Martha belonged to was one kind of Judaism that affirmed that there would be some sort of resurrection of the dead. And Martha said, yes, I do believe this. I really do. But you know what? Like the person in the letter said, I know that good things come out of difficult times, but it's not enough. If you had been here, I think my brother might not have died. Martha and Jesus and Mary all understood, um, that you can still have faith and at the same time be really mad. Be really sad. Feel that that faith, which sustains us at sometimes, also doesn't answer all the questions that we have. It's okay to be a person of faith and to say, I'm really sick of people dying. It's okay for both things to be true.

Jim Mitulski: After Jesus and Martha had, had this exchange, Mary then, uh, met with Jesus, and it says, perhaps she was remembering the conversations that they had, had earlier, many important ones, and she ran to meet him. And as they discussed, she said the same thing.

Jim Mitulski: I really miss my brother. I wish he were still alive. I wish he hadn't died. And so she said that, uh, to Jesus. And it says that when Jesus saw her weeping and the religious people around them saw her weeping, that Jesus groaned in his spirit and was troubled. And he also wept. And it's so important that we believe that Jesus was capable of crying. For Orthodox Christians, and I'm not sure I am one anymore, I don't think I am, but for Orthodox Christians, um, Jesus was seen as the embodiment of God, the embodiment of the divine. And part of our faith is that we can believe that God is one who cries with us when we cry, who weeps with us when we weep, who really feels heartbroken when we feel heartbroken about the loss of someone that we love.

Jim Mitulski: This feeling that Martha and Mary and Jesus kept sharing with one another, if I had been here, maybe this wouldn't have happened, I think is an important spiritual thing for us to think about when we confront the possible loss of either our own life or of those around us. It's not our job to save people from dying. We can't do it. We can't control it. It's really hard to admit it, but we really can't control it, no matter how hard we try. It doesn't mean that our attitude isn't important, and that our support for one another is not crucial or pivotal in how we go through this experience together. But there's an important control issue here around acknowledging that our own efforts are not what make the difference solely. Um, it's not our job to prevent people from dying. We can't do it.

Jim Mitulski: Um, one of the most poignant things that someone has ever said to me in the six years that I've been here was the doctor who said to me when his friend was dying, I'm a healer and I can't save my friend. And he felt that failure almost in himself, even though that wasn't the whole story.

Jim Mitulski: The people around Jesus and Mary and Martha contribute to this environment of blaming. They say, couldn't this one who opened the eyes of the blind have saved his friend? I believe that that's a community of people who were toxic with the feeling of, I'm really tired of people dying. I can't stand it. Not one more moment, not one more day, not one more person. I can't stand it.

Jim Mitulski: What happens in this story, the way this story is resolved is that, um, It's not the way it happens for us, I think, but the way the Bible story goes is that Jesus comes to where Lazarus is and says, Lazarus, come forth. And then it says that the one who was dead came forth, and he was bound hand and foot. And Jesus said, Loose his binds and let him go. And that's the part that I think we can do for each other. The loosening of the bonds that keep us, the letting go of the feelings that we repress, creating an environment where we can free one another to express whatever feelings it is that we feel right now.

Jim Mitulski: There is no precedent for what it means to live with this level of grief. I don't think I can say that enough. I don't think I can grasp it enough for myself. That's probably why I say it so much here. I don't think human beings were meant to live with this much suffering, grief or loss. And it's very hard and there's no way to do it right or correctly or perfectly.

Jim Mitulski: But one thing that we can do for one another, the way that resurrection or new life happens for us in the midst of the life that we do have, is that we can take turns caring for one another and loosening the bonds that keep us repressed or keep us, um, down. We can express all the feelings that we have right now.

Jim Mitulski: Anger. I'm really starting, I think I'm about to enter my anger phase. I don't think I can cry too much more, you know. If you, if you know what I'm talking about, you know what I'm talking about. Um, I, I do it a lot. It seems I go through days where I do it quite a bit. And yet, I just don't think I can do it anymore. And I don't think God expects us to do it anymore. Um, God is there to cry for us when we can no longer cry. And right now, God's anger and God's passion for justice is expressed through us in our own anger. Numbness, another feeling. I don't think I can stand to feel numb anymore. And yet, that's one of the defenses that we have when we are sick of people dying. And sadness, too, is one that continues to be a part of our lives, the fabric of our lives.

Jim Mitulski: There's no answer to this feeling of what to do when we're sick of people dying. And yet I know the most important thing that we can do, the thing that's within our control, is to find ways for us all to express the depth of our sorrow, and our grief, and our anger, and our numbness, and our tears, and our laughter too, when that's appropriate. Um, that's the best gift we can give each other at this time. The lesbian poet, Adrienne Rich, says in one of her poems, There must be those among whom we can weep and still be counted as warriors. The church and communities like it are places like that. A place where we can come together, where we can weep, and where people will still recognize that we are warriors. I don't know that I like the imagery necessarily of a fight or a war against AIDS, and yet, this is, that's how it feels sometimes, and it's not a fight. A fight I want to lose or that I'm willing gently to let, uh, one more person be lost into.

Jim Mitulski: Expressing our feelings is the, is the one thing that we can do. And channeling it into action is something else that we can do. Demonstrations, political action, supporting the community, giving money. These are all ways, small ways that we have of breaking out of the paralysis that can take place in us when we feel that we're sick of people dying,

Jim Mitulski: we can't stop people from dying. Every one of us will die. I know we know that. We say it a lot. It's one of those things we say to comfort ourselves. I don't know why we say it. But it does, it's true. All of us face that. Some of us have HIV. Some of us don't. None of us want to die, it seems. But this is a place where we can still come together week after week after week and weep and still be counted as warriors. A place where our relationships can continue to flourish. A place where we can still continue to know love and to live life fully as long as we have it, until it's over, and even then I'm not sure it's ever over.

Jim Mitulski: There's, uh, I want to close with, um, pointing out to you some verses, uh, a hymn that we're going to sing during communion. And we sing this song, Old Devil Time, by Pete Seeger quite a bit here in our church. It's like one of our theme songs. And one of our church members, Paul Francis, my theologian of choice lately it seems, wrote two new verses for it that Pete Seeger didn't write, but that Paul Francis wrote. And they're here, the fourth verse and the fifth verse.

Jim Mitulski: Old devil AIDS, I'm gonna beat you now. Old devil AIDS. You'd like to keep me down. When I feel ill, my lovers gather round and help me rise to fight you one more time. Old devil death, I'm gonna cheat you now. I'm gonna rise and live my life with love. When I feel you come, lovers will gather round and help me rise to fight you one more time.

Jim Mitulski: There's no answer to the question that I pose about what it means to feel like you're sick of people dying. But I know that the support that we have in this place makes living the life fully that all of us have possible and abundant. I invite you to become part of that group of lovers who gather round. Whenever we need it, for whoever we need it, so that we can rise to fight this one more time, until it's over.

Jim Mitulski: Amen.

Lynne Gerber: Next time – a church romance between a hula dancer and the Rock Hudson of the forest.

Bob Lawrence: he was, uh, um, this part needs to be bleeped on the recording. He was hot as –

Cees Van Aalst: I Mean, he really was a hunk. He was a very good looking man.

Dennis Edelman: He was a lumber sexual.

Lynne Gerber: Oh, yes. One of my favorite varieties. Yes.

CREDITS

When We all Get To Heaven is a project of Eureka Street Productions and is distributed by Slate. It was co-created and produced by me, Lynne Gerber, Siri Colom and Ariana Nedelman.

If you love the show, we’d love your help. The best way for new listeners to find us is through word of mouth. Please spread the word and tell folks about us. The next best way is through listener reviews. Please review us on whatever app brought you here. Thanks so much!

Our story editor is Sayre Quevedo. Our sound designer is David Herman. Our first managing producer was Sarah Ventre. Our current managing producer is Krissy Clark. Tim Dillinger-Curenton is our Consulting Producer. Betsy Towner Levine is our fact checker. And our outreach coordinator is Ariana Martinez.

The music comes largely from MCC San Francisco’s archive and is performed by its members, ministers, and friends. Additional music is by Domestic BGM.

We had additional story editing support from Arwen Nicks, Allison Behringer, and Krissy Clark.

A lot of other people helped make this project possible, you can find their names on our website. You can also find pictures and links for each episode there at – heavenpodcast.org.

Our project is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, the E. Rhodes and Leona B Carpenter Foundation and some amazing individual donors. It was also made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. You can visit them at www.calhum.org.

Eureka Street Productions has 501c3 status through our fiscal sponsor FJC: A Foundation of Philanthropic Funds

And many thanks to MCC San Francisco, its members, and its clergy past and present – for all of their work and for always supporting ours.