Conversion

Episode 8

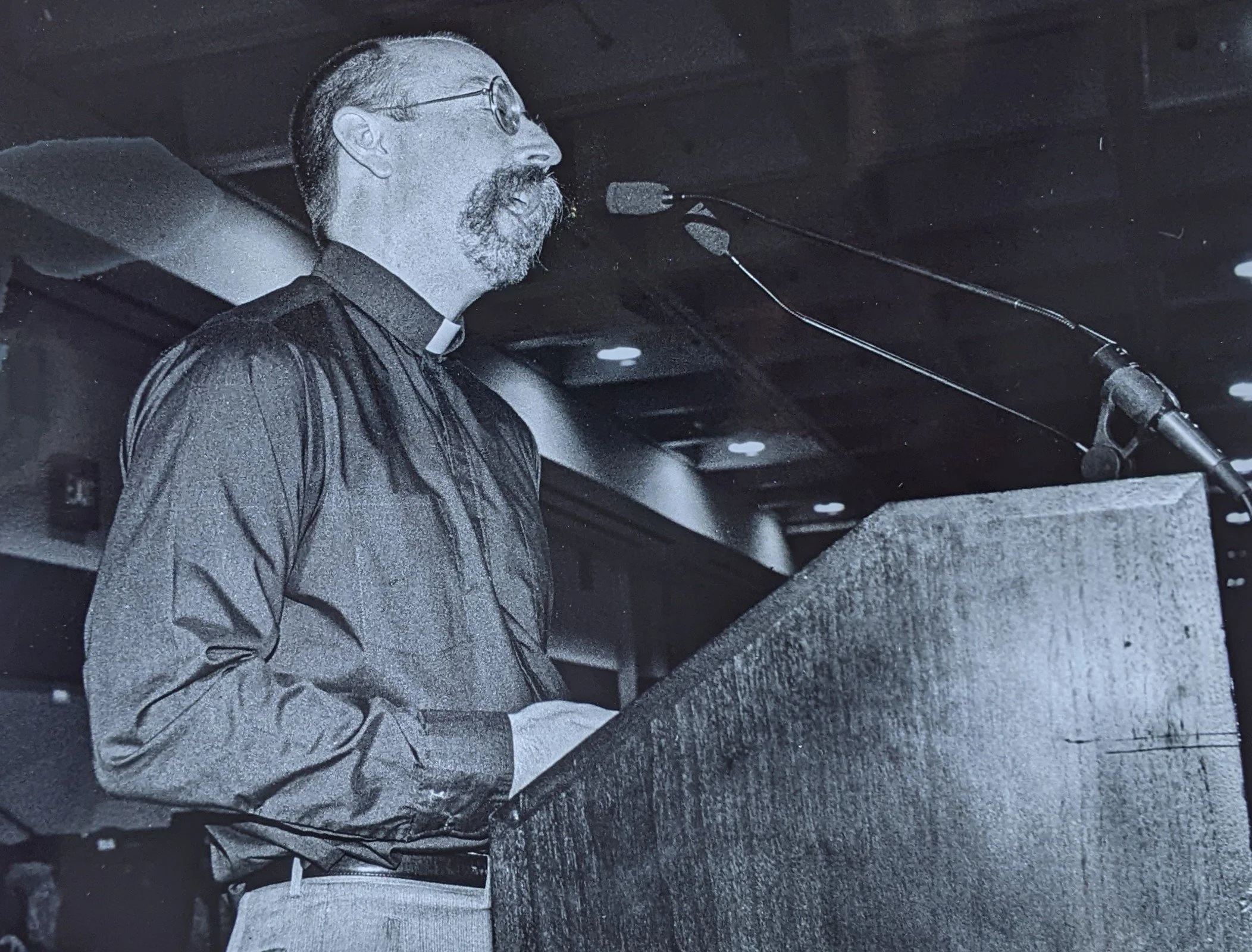

Rev. Jim Mitulski. Date unknown. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco collection, San Francisco Public Library.

In 1995 Rev. Jim Mitulski became HIV positive—what's known as seroconversion. It was 14 years into the epidemic and people knew what HIV/AIDS was, how you got it, and how you could prevent it. And when Jim got sick, he got very sick. What was it like to become ill so publicly? How would the church and the community respond? And what could Jim possibly preach about on his first Sunday back?

NOTES:

NOTES

Gay psychologist Walt Odets was one of the first to study the way the epidemic impacted HIV-negative men. He wrote about it in In the Shadow of the Epidemic: Being HIV-Negative in the Age of AIDS (Duke University Press, 1995).

Eric Rofes was gay AIDS activist who wrote extensively about gay male life in the 1990s. He saw it as an optimistic time and sensed a community about to be reborn. He was also a friend to MCC San Francisco and preached there on occasion. His books include Reviving the Tribe: Regenerating Gay Men’s Sexuality and Culture in the Ongoing Epidemic (Routledge, 1996) and Dry Bones Breathe: Gay Men Creating Post-AIDS Identities and Cultures (Routledge 1998).

The biblical story of the death of the prophet Elijah is in Second Kings, chapter 2.

Music:

“My Soul Doth Magnify” is from Camille Saint-Saens’ Christmas Oratorio, Op. 12, 1858.

“The 23rd Psalm (Dedicated to My Mother)” is by Bobby McFerrin.

THANKS

Thanks to Ed Wolf and Frank DePelisi for talking us through the issues around HIV status and sero-sorting in the mid-1990s.

And thanks to Bobby McFerrin and Linda Goldstein for use of “The 23rd Psalm (Dedicated to My Mother).” You can see McFerrin conducting his VOCAbuLarieS singers singing the piece here.

Resources:

National Resource Center on HIV and Aging – resources for older adults living with HIV.

Surviving Voices – an oral history documentary project on how different communities have experienced HIV and AIDS. The most recent focuses on lifelong and long-term HIV survivors.

Let’s Kick Ass – AIDS Survivors Syndrome – support for long-term HIV survivors.

TRANSCRIPT:

Episode 08 – Conversion

NOTE: This audio documentary podcast was produced and designed to be heard. If you are able, do listen to the audio, which includes emotions and sounds not on the page. Transcripts may contain errors. Check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Jim Mitulski: How I became HIV positive, I could write 10 different stories and it could all be true.

Lynne Gerber: In 1995 Jim Mitulski-- pastor of MCC San Francisco, preacher of compassion, minister at countless AIDS funerals -- got sick. And when he got sick he learned he was HIV positive. Fourteen years into the epidemic. In a moment when pretty much everyone in San Francisco knew how a person got it. And how a person might prevent it. A lot of people had a lot of feelings about Jim getting sick and getting sick in that moment. Jim most of all.

Jim Mitulski: Well, we just kept trying to find meaning, meaning, meaning, you know, every, every moment has meaning. I mean, this was the key to our survival and it was the downfall too. We only live in the present. We only live for the present. The present has all the meaning it needs and has. On a good day that kept us motivated to live one more day. On a bad day, it made us [00:01:00] reckless about our futures.

Lynne Gerber: A lot of times illness is laden with moral meaning. We tend to think a person's illness means something about their character. But with AIDS it was a whole other level. Because the ways AIDS was transmitted -- through sex and drugs -- were tied up with sin. And disgust. And making AIDS about disgusting sinners made everyone else imagine a measure of safety from its terror. However cheap that grace.

Lynne Gerber: MCC worked constantly to try to make different meanings from AIDS. They resisted condemnation and they resisted shame. They lived AIDS and in the living tried to find new ways to make sense of it. At times they even recognized its gifts and tried to honor them.

Jim Mitulski: Someone said to me recently, Paul Francis actually, he's a member of our church with AIDS. He said that next month he's celebrating a [00:02:00] third anniversary of his diagnosis with AIDS, and he wanted to have a party. And he wondered whether or not that would be in bad taste. I said to him, don't be silly, we are homosexuals. We determine taste. We say it's in good taste, it's in good taste. And then the whole world, the whole world stands by and goes, Ooh. For him, he said, this has been the best three years of my life. It was a truth, a hard truth, For me who loves him, um, to accept, even. To let go of and to accept.

Lynne Gerber: The church used every ritual and theological and social and aesthetic tool in the church-making tool kit to reinscribe AIDS, resist its moral stain, and find [00:03:00] better meanings -- meanings that would help people live. Or die or grieve with less shame and less fear. And when Jim got sick, that was put to a very public test.

This is When We All Get to Heaven. Episode 8 – Conversion. I’m Lynne Gerber

Lynne Gerber: When AIDS came on the scene in the early 1980s, when it was clear that sex had something to do with its transmission, many people, especially religious leaders, proclaimed that abstinence was the answer. Religious conservatives had long been suspicious of sex, especially sex that was openly discussed, pursued for pleasure, and not aimed at making babies. That suspicion runs deep in American culture.

Lynne Gerber: But gay men, especially in San Francisco, were not going to demonize sex. They fought too hard to have it, to have it without shame, and to claim that it was good. They were going to figure out how to keep having sex while keeping themselves and their partners safe.

Kitt Cherry: I also have a special guest who's going to be at the social hour at [00:04:00] the program fair, appearing on behalf of AIDS ministry, promoting safe sex. Our visiting nurse.

Lynne Gerber: Their visiting nurse was Lynn Jordan. He was a church deacon, dressed in full nursing drag.

Lynn Jordan: I'm everybody's answer to safe sex, in some cases probably total abstinence. I'm going to be your latex hostess for today. I'm going to be passing out condoms, dental dams, rubber gloves. So whatever you have in mind for this evening, see me, I'll be watching you.

Lynne Gerber: In San Francisco, queer safe sex advocacy started with a pamphlet called Play Fair! in 1982. It was written by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a campy order of queer and trans folks in nun drag whose [00:05:00] mission is, and I quote, to "promulgate universal love and expiate stigmatic guilt." These are not Catholic nuns. Play Fair gave some safe sex basics and pointed readers to gay-friendly places to get diagnosed, treatment, or support -- including MCC.

Lynne Gerber: The Safe Sex gospel took hold in San Francisco. Gay men were committed to keeping their community safe and stopping the spread of HIV through knowledge and mutual support. They got latex into people's hands, information into their heads, and experimented with making safe sex hot. And it made a real difference. By the late 80s HIV transmission rates had dropped significantly among gay men. At least one organization devoted to changing sexual practices claimed victory and left the field.

Lynne Gerber: But by 1990 it was clear that declarations of victory were premature. Safe sex wasn't a message you just got once and forever after put into practice. And there were a lot of people at [00:06:00] risk who had never heard the message at all.

Jim Mitulski: It was a darker period, 90 to 95, the knowledge was saturating that there was no cure, and the numbers were increasing

Lynne Gerber: AIDS is often remembered as an 80s thing. A Ronald Reagan, Moral Majority thing. At the least the hardest parts of it. People remember AIDS in the 90s, but it's often remembered as somehow easier, less stigmatized, with more possibility for change. And sure, by the early 90s so much was changing, all over the world. The cold war was over, democracy and freedom prevailed. A democrat was elected president! And he talked about AIDS as a priority in his campaign! The 90s would be different.

Lynne Gerber: But for many of those who went through it in gay San Francisco, the early 90s were the bleakest. It was the height of AIDS deaths in the city. Loss and grief just kept coming. And every seeming hope proved short-lived. Safe sex had developed its own moral overtones. It could seem so simple a solution, so evidently true, so easy to put into practice. But nothing's easy to put into practice when fear and shame and loss pile up. When joy and pleasure and connection need to be found. And when a community starts to make social meaning from differences in viral status – by limiting who they date, who they have sex with, or even who they socialize with.

Jim Mitulski: The topic is, are you positive or negative many of us gay men and lesbians, men and women both, have taken HIV tests. Many of us know our HIV status, and some do not. It's as if there are two realities right now, positive and negative. Two coterminous realities, two different ways of being and ways of experiencing the world [00:08:00] that are happening at the same time, in the same place, with the same people.

Lynne Gerber: In 1992 Jim talked about his own HIV status from the pulpit for the first time. It was three years before his diagnosis.

Jim Mitulski: Um, I am a person who is HIV negative and I also move because of my work in many circles. Um, I've been in parts of HIV positive groups And often people can see in me whatever they want to see. and so I really have kind of a perspective on both.

Lynne Gerber: He did it because he had recently been diagnosed with Hepatitis A. And when he told people, he got a taste of just how intense the moral charge around contracting a sexually transmitted disease was. Even -- or especially -- in the Castro.

Jim Mitulski: Many people would say, oh, did you have a good time getting it? Or, they would, no, this is true. Or they would say, One person said to me, well, that'll teach you to use a condom every time, very seriously. one person mailed to the church office, in case we didn't have this information available to us, an article from the Chronicle with the sections about [00:09:00] how a person gets, Hepatitis A, underlined, so we would not miss this, uh, information.

Lynne Gerber: This community was always pushing back on what society was telling them about AIDS. But the question still gripped people. What did AIDS mean? What did it mean about them personally? Morally? Spiritually?

Jim Mitulski: We have in our community, um, as much, I think, unprocessed issues around the meaning and the moral meaning of HIV status as we might as if we were a Presbyterian church on the peninsula, even though we're a gay and p lesbian community here.

Lynne Gerber: He also shared another intimate thing about his life in that sermon. One that made the stakes in the positive/negative distinction deeply personal.

Jim Mitulski: The thing that has most caused me to think about the meaning, if you will, of HIV positive and HIV negative is this thing. And this is very hard to share with you, but it feels very important for me to do it. It's almost a separate sermon, but I just, I think it's [00:10:00] worth doing. And that's this. I have a boyfriend who is HIV positive and who has AIDS. And this is not Bob Crocker, who is also my boyfriend.

Jim Mitulski: And I realize that this situation in my life right now is the most, um, important emotional thing going on in my life. Someone that I love very much is dying, even as we speak. Um, it's where my heart is right now. And, uh, I, in tangentially to this, I realized that I, I was so worried that what people might think about me for having more than one boyfriend, as if I'm the only person in the history of humanity that has done this, Um, that I was, uh, afraid to tell people about what's been going on for me emotionally.

Lynne Gerber: This is Bob Crocker. Jim’s boyfriend. And MCCs music director.

Bob Crocker: Jim had the habit of going out for milk for nine months or a year.

Lynne Gerber: He and Jim were open in their relationship -- privately, and then publicly.

Bob Crocker: We were open about our sexual friendships and, romantic friendships with other guys. Our relationships were very public and widely seen, so there was no point being cute about it. We also saw the toll that having secret relationships took on people and it just wasn't necessary anymore for God's sake. You know, this, it's 1992, we don't need to do this anymore.

Lynne Gerber: Secrecy about the multitude of queer intimacies kept people from each other. Lovers from lovers. Ministers from their congregation. And it increased the [00:11:00] risk of transmission. If people were going to be able to give and receive support, they needed to know what was actually going on in each other's lives.

Bob Crocker: He was sacralizing a relationship that's like that.

Lynne Gerber: A relationship that was one in a complex web of relationships. And [00:12:00] that crossed the lines of HIV status. But whose impending loss was no less painful and no less deserving of care.

Jim Mitulski: I pray for you that you can find in your heart a place where whether you're positive or negative in terms of antibody status, you can say, that will never separate me from the people around me. I can tell you as a person who loves a person with AIDS that I would never, ever give up a minute of the relationship that we have had. Not one minute.

Lynne Gerber: The early 90s was a moment when sero-status -- whether a person was HIV positive or HIV negative -- was rife with meaning. A lot of people had access to the test, and were taking it. So folks often knew what their status was. A lot of attention was being paid to people who were HIV positive. For obvious reasons. And new attention was being paid to people who were HIV negative -- [00:13:00] in part to help them stay that way and in part because people were starting to realize that HIV negative men were going through their own kind of psychic nightmare. Some called it survivors guilt, some called it compound grief. But most of the time it didn't have a name -- and it could easily be overlooked by the immediate and overwhelming needs of folks who were actively sick. People with different sero-statuses were experiencing the epidemic differently. And that real difference could become really problematic when people attached moral value to HIV status -- and started to segregate by that status. Those were the kinds of meanings about positive and negative that Jim was trying to push against.

Jim Mitulski: Positive or negative has a certain medical reality. It does not have to have a spiritual reality in a way that separates us one from the other. It does not have to have a political reality that says there are two kinds of people in the world and they can never be together. Um, [00:14:00] it, it does have a medical reality that's important. And it's not a bad reality. Neither one or the other has moral value in my opinion. the question for us, do we want to be positive or negative or are we positive or negative? It isn't about antibody status, it's about do we want to be hopeful or give up hope? Do we want to be committed or do we want to feel resigned? Can we bring ourselves to not give up on each other and not give up on God until such time as we experience the healing that I believe is God's will for us? I think it's important for this church and for this community to remind ourselves time and time again, God does not send illness, God does not punish us through illness, these are not judgments on us, but rather God's role in this is hoping with us, praying with us, experiencing with us the pain and also the joys when they happen that, that having the reality of positive and negative in our community means right now.

Lynne Gerber: Not giving up on each other and not giving up on God. That's what Jim wanted to point people toward. And what the church wanted to make space for. Because so many forces were pulling people -- and God -- apart.

Lynne Gerber: By 1995 Jim really needed a break. He was eight years into his ministry at MCC San Francisco. And he was tired.

Jim Mitulski: Tomorrow morning, I'm getting in my truck and driving to Boston. And, uh, very excited about this. I begin a four and a half or so month sabbatical that, I've been preparing for for some time.

Lynne Gerber: He got a gift for the road.

Jim Mitulski: She got me this, coffee mug. It's, it's, uh, It's the sort of thing tourists buy often, San Francisco, my favorite city, where the women are strong and the men are pretty.

Lynne Gerber Jim was going to Harvard Divinity School for a semester. A continent away from the Castro and the church. Five months without [00:16:00] hospital visits or sermons or funerals.

Bob Crocker: I think he needed to be away from all the, uh, from all of it for a little while. And also to have the opportunity to really think about all of it,

Lynne Gerber: He left the church in good hands. There was Linton Stables, who had been the chair of MCC's board of directors and seen the church through many crises, including the Lynn Griffis ordeal from episode six.

Linton Stables: What would Easter be without the Easter parade and the parade of bonnets?

Lynne Gerber: There was Maggie Tanis, the associate pastor, who stepped up in Jim's absence. This is Maggie talking about Moses encountering God at the burning bush.

Maggie Tanis: So he asked God for something to tell the people. A name for God, so they will know who sent him. And God answers, I am who I am. Which can also be translated, I am what I am, or I will be who I will be.

Lynne Gerber: Our archival tape recorded Maggie's voice. And when we interviewed him, years later, he had become Justin. We asked him what he wanted to be called in this story and he told us he's comfortable with the historical use of his name. So when we talk about him in the archival tape he's okay with us calling him Maggie. And in the interview tape he's Justin.

Lynne Gerber: There was Bob, Jim's boyfriend. Or one of them. And the church's steadfast musical anchor.

Lynne Gerber: And there was Penny Nixon, a longtime east coast Presbyterian minister who had recently come out as a lesbian and moved to San Francisco. She preached at MCC once or twice before Jim left and once or [00:18:00] twice while he was gone.

Penny Nixon: I said. So Bob, did Jesus really rise from the dead? And in his inimitable way, he said, that's an interesting question. And then he said, something happened. And I thought, now that's profound.

Lynne Gerber: The four of them held the church in place so Jim could go. It was time for him to take a breath, catch up with himself, reflect on his ministry, and come back refreshed.

Jim Mitulski: 95 I go off to Harvard for a sabbatical. I get to Cambridge, I'm sitting in a, um, theater, the movie theater that was there,[00:19:00] and watching little women, which had just come out the new one. I mean the new one at the time.

Lynne Gerber: Yeah.

Jim Mitulski: And watching how, um, like the one young one dies, and it was just like, I just had a freaking nervous breakdown. Um, I mean, I was sobbing uncontrollably. Because it was little men. and I, I think that it was very hard. The only way I coped, and I think this is true of some others, during that period was you just had to soldier on. And when I stepped out of it for six months, I knew I was coming back. I allowed myself to feel for the first time the, the, what I was feeling, what I'd been suppressing.

Lynne Gerber: But Jim did more than just fall apart at Harvard. For the first time he actually studied the epidemic he was living through. He took a course on AIDS with Jonathan Mann, a physician who founded the World Health Organization's Global Programme for AIDS and then resigned when the United Nations didn't respond to AIDS adequately.

Jim Mitulski: So I've been living in AIDS and I'm a reader as you know, but I'd never studied AIDS itself epidemiologically or even from sociological perspective around race, class, gender, and the economics, uh, even the science of it that much.

Lynne Gerber: The class put the last decade plus of Jim's life and ministry into an analytic framework. And the more he understood the politics of AIDS, the more he wanted to respond politically. When he came back from Harvard in June of 1995 he was heading toward a more publicly engaged ministry.

Jim Mitulski: That's when, if you look in the newspapers and television and all those things, that's when I was doing things like, protesting and, I took it to the streets.

Lynne Gerber: But it wouldn’t happen right away. First, everyone had to deal with the strangeness of him being back.

Jim Mitulski: I love being back, but, you know, like walking into the house and having Bob look at me like, Who are you? And what are you doing here? It's not a bad thing, it's just a weird thing.

Lynne Gerber: And then, just when he got back, he was gone again.

Lynne Gerber: Three weeks after Jim's first Sunday back, Maggie made this announcement.

Maggie Tanis: We also wanted to let you know that Jim Mitulski, who is our senior pastor, is in the hospital right now. Uh, Jim has an infection, um, and he's currently in intensive care so that they can closely monitor, uh, the treatment of that infection. He is receiving aggressive treatment right now. Um, He is not able to receive any visitors or phone calls right now So we ask that you not call or stop by but please do contact the church and we'll give you information as we have it There are cards for you to sign and notes up that will be available at the social hour today I know Jim would love to hear your get well greetings and information from all of you.

Lynne Gerber: Justin told me about it years later. From here on out, Justin, not Maggie, is the voice you'll hear

Justin Tanis: So then Jim came back, um, and he was at, we were at a staff meeting and he, and he said, I, you know, I feel a little queasy.

Lynne Gerber: Steve was the church admin person. He remembered it too.

Steve Marlowe: And we put him in my back seat I, I remember being on the freeway, and I don't know where, I don't remember where we went, and I don't remember how long, I remember being there going, oh shit, he's sick, I had a little four cylinder Toyota, uh, he looks so small in the backseat, he looks so, I kept looking up and going, he's so small. And I don't mean he lost weight. I mean, he was, he was like this tall in the back, you know, that's, that's what I saw. And, uh, I've never prayed and drive driven at so much at the same time.

Lynne Gerber: Jim remembers . . . . some of it.

Jim Mitulski: I remember dying. I remember he's coding, uh, and then fade to gray. Cold gray. No warm light. I remember saying, I can't be sick. Um, my desk is a mess. Uh, Penny should preach on Sunday and that was, and I signed out. Those are true. People heard them. Heard me say those things. Uh, those are my last words. Penny's preaching on Sunday. Thank God it wasn't the end.

Lynne Gerber: These were people who knew their way around hospitals. Jim's friends set up shop.

Justin Tanis: He was at Kaiser ICU, we were, we had a camp, we had this whole, like, area of the lounge where we'd all camped out.

Lynne Gerber: And they had some questions.

Justin Tanis: people were asking if he had AIDS and we didn't know.

Lynne Gerber: Were you aware of your HIV status when you went to the hospital?

Jim Mitulski: No, I thought it was, I thought, I mean, my last test for that way had been negative. Two years before. Um, and it happened very quickly. I mean, I was, I did have E. coli and it got, I became septic. I think it's the word. I'm never quite sure that what the terminology means, but somehow it got into my bloodstream. So that caused an accelerated infection.

Justin Tanis: At that Sunday, it wasn't clear he was going to live.

Lynne Gerber: For a while no one really knew what was going on. They had suspicions, but they didn't know for sure. Troy Perry flew up from Los Angeles to see Jim for himself.

Troy Perry: I want to just tell you that I'm going to leave after I pray to go over to the hospital. I have to fly back to Los Angeles this afternoon. Uh, Jim is in good spirits. I knew that and is really fighting this infection, whatever it is really well.

Jim Mitulski: Felt my grandmother's presence. Um, rosary during this period of a couple weeks when I was not conscious. Troy Perry visited, and I remember it. But I didn't know it. I wasn't conscious. But I knew it. And I remember thinking, uh oh.

Lynne Gerber: They had to tell the church something. Even if they didn't know exactly what to say.

Justin Tanis: We felt like keeping it a secret would have If, if we had to tell people later, particularly if he died, it would have broken trust with the congregation. Yeah. That's particularly one that was so wrapped up in issues of death and dying. At the same time, this congregation was so wrapped up in issues of death and dying that we didn't want [00:26:00] to unnecessarily frighten them if he was going to be okay.

Lynne Gerber: And then they just waited to find out what was wrong. And if he'd get better.

Justin Tanis: It was when he was in Kaiser that he was HIV tested. because I distinctly remember that waiting period of, we didn't know what was wrong with him, and he was waiting for, you know, that horrible wait for the HIV test.

Lynne Gerber: Jim remembers it a little differently.

Jim Mitulski: Afterwards, in the aftercare, that's when they told me I was HIV positive. In fact, I had to go back to the hospital. Now, everyone else knew it. They told them all. All my friends knew it, but they never told me. And you can imagine the chagrin. And I remember to this day, the guy said, Well, you know, you are HIV positive. And, um, I immediately started sweating and turned bright red. Um, and my friends knew this. And I was partly, I was embarrassed.

Lynne Gerber: Jim was in the hospital for weeks. He was newly diagnosed. And he had had multiple surgeries that meant he had to recover at home for a while longer. But the healing he remembers most viscerally from that time wasn't physical. It happened when Patrick Horay, a church deacon, visited Jim after he was home. Patrick brought a friend with him – a monk from a local monastery.

Jim Mitulski: And, um, I told him I was, um, weighted down with shame and I couldn't get better. Because I was so ashamed. And, um, They laid their hands on me and prayed for me. And I heard, the beating of wings. And, um, I felt, it lifted. And that's, it was then that I started being able to walk up to Cortland Street.

Lynne Gerber: And when he started walking he started ministering to folks again, even before he went back to work. Because AIDS wasn't waiting for him to get better.

Jim Mitulski: Even though I was motivated to get back and I didn’t want people to think I was dead because that was what, you know, that's what happened then. This was before protease.

Lynne Gerber: Protease inhibitors were the first effective treatment for AIDS. They were being tested in 1995, and they would change the world soon. But not quite yet.

Jim Mitulski: Just a year before protease, but it was in that period of, uh, people died and you just never saw them again.

Lynne Gerber: During the time he was too sick to work, four people he was close to in the congregation were coming to the end. One was a man so close to death that folks told Jim he had to visit.

Jim Mitulski: I couldn't climb steps. I crawled up [00:29:00] steps, uh, because of my stomach had been, uh, opened, and who knew it affects all kinds of muscles, you know, that you don't think have to do with your stomach. So I couldn't walk. Couldn't get up. That was the problem. Couldn't stand up. Had to be lifted. So I crawled up the steps to his little house in Bernal Heights and damned if we didn't pray with him and, you know, he died. And this is all while I was still recovering.

Lynne Gerber: AIDS wasn't waiting for anyone.

Lynne Gerber: When I asked Jim, in recent years, how he understood how he came to contract HIV so late in the game, you may remember what he told me.

Jim Mitulski: I could write 10 different stories and it could all be true.

Lynne Gerber: Here's one.

Jim Mitulski: One is in a period where we stressed living in the present, I became reckless and, um, thoughtless in my incapacity to believe I had a future or care about a future and engaged in sexual practices that, um, [00:30:00] you know, led to my becoming HIV positive because I had feeling and feeling in the present was more important than a future I couldn't see anymore.

Lynne Gerber: Here's another one.

Jim Mitulski: Another version of the story is I fell in love with someone, who was, uh, such a, was such a compelling emotional bond and sexual bond that even today it's a standout in the story of my life who was HIV positive. And, uh, for a period of time we engaged in, sex with condoms and then we didn't. And no regrets. Complicated. Yeah. Who was a dear friend of mine. Without really thinking about it. Or it was our secret. It was our bond. I mean, you can say it was fucked up, but you know, love in the midst of cholera.

Lynne Gerber: And another.

Jim Mitulski: I think I, because of my personality, this is not very attractive from a, psychological standpoint, but my always strong sense of identity with the groups with whom I work, whether it's immigration or, homelessness or, um, women causes me such a strong identification, and I have this capacity that is a source of strength and passion, inspiration, rigor, creativity. Also, I lose any sense of boundary or self protection. Become part of the cause that I'm committed to. Hard to explain? Definitely true.

Lynne Gerber: And another one still.

Jim Mitulski: Also I was young in my thirties. We were invincible. We were taking on the world. Yeah, We were not gonna die.

Lynne Gerber: These are all stories, understandings, perspectives that he's, thankfully, had years to reflect on, to process and to understand. But in that moment, at the time he got sick, there wasn't that kind of time or that kind of space. Because a lot of people were grappling with their own efforts at making meaning.

Jim Mitulski: I remember people were mad at me, and this is a phenomena: today's HIV negative person is tomorrow's HIV positive person.

Lynne Gerber: For some people it was the terribleness of yet one more person to be with in their sickness and to possibly lose.

Kevin Fong: You know, it's just like, I'm going to cuss. Oh fuck Just another, another, now this, right?

Steve Marlowe: No, Jim, you can't go. I've seen this. I've seen this movie. I've been in the movie over and over again. All the chapters. All the series. Uh, no. No, no, no, no, no.

Lynne Gerber: Others were frustrated. Linton had been on the board, keeping the church going administratively for years, doing the most thankless tasks, through crisis after crisis.

Linton Stables: I didn't tell anybody this, but, you know, I was, and I didn't even tell him. because I mean, honestly, one could have said that about any person that came down with HIV, but it's, it's not fair. Not fair to Jim for me to, to have thought that, but at any rate, I was, I was angry at, and it also extended the time that I had to do that job,

Lynne Gerber: There were the daily, mundane questions that had to be attended to. Bob took on a lot of those.

Bob Crocker: What should we do with the house? What about insurance? What about mom? People were pretty straightforward about things like that. What about my car? We have to remember that everybody lived with the possibility of death.

Lynne Gerber: And then there were the moral questions. Why would a pastor not practice safe sex? How could a church leader not know better? What did it mean that he didn't? Lynn Jordan, the safe sex nurse, remembered the double standard that folks held church leaders to.

Lynn Jordan: It was interesting even within the context of the church too, that as some of us assume various positions, that there were certain expectations that somehow, um, we had to be above the others in terms of our moral behavior. Let's put it that way. And I certainly wasn't. [00:35:00] So, there was that kind of, and especially among, they were holding the, those of us who were deacons and the pastors were held to a higher standard by some of the members of the church. So, we had that conflict within the church itself at times. I mean, they were hanging, I was running into them in the same places, at the bars and the baths, but like, what are you doing here? Hello?

Lynne Gerber: And Penny and Justin remembered how the topic of safe sex had become charged in the congregation.

Penny Nixon: Now that's that's an interesting thing. Was safe sex really talked about much from the pulpit? No Because we because probably Uh I didn't know where my place was because it wasn't the women that were getting sick. Because we had so much stuff coming down at us from religious groups and this and it, like, it just, [00:36:00] I don't know.

Justin Tanis: I think that there were some people in the congregation who were angry with him. And I would say there's probably plenty of people who also, who knew very well why we know that people aren't perfect in their, I mean that condom use isn't 100 percent.

Lynne Gerber: And for some, it made them feel like Jim understood them even more.

Justin Tanis: I Do remember one of the members of the congregation who had HIV talking, this was sometime after he got ill. essentially that Jim became, you know, one of us, in that man's eyes. somehow the fact that someone shared your circumstances put them in a different place of ministry in regards to you.

Lynne Gerber: There was only one response that Jim remembered sticking with him for a long time. Or at least that he told me. From a close friend who told Jim he wouldn't visit him in the hospital [00:37:00] because he was too angry.

Jim Mitulski: A year later, on, uh, on Yom Kippur he wrote me a letter apologizing. It was hard to accept, I did not find it easy to forgive him.

Lynne Gerber: But Jim had to do something that not a lot of other people had to do right after they found out they were HIV positive -- and that their HIV had progressed to such a serious point. He had to get up in front of a congregation that he had been leading through AIDS -- people whom Jim had visited in hospital rooms of their own, people who Jim sat with as they lost lovers, people whose partners' funerals Jim had preached at. And he had to talk to them about his experience in a way that was true. In [00:38:00] a way that made meaning from his experience and that didn't feel like bullshit. Because these people could smell bullshit from miles away.

Steve Marlowe: And more, what overshadowed him actually being sick is talking about it. From the pulpit. And, and, didn't hide it, he was authentic. I don't know how the hell he did that. He was sick and I was hiding. But he got up and, and talked about it. And I think that was what, what got a lot of people through. Was, was look, there ain't gonna be no secret.

Penny Nixon: Well, you know, he was iconic for a couple of things. One, just because of who he is. And two, you step into something and you rise to the occasion. He stepped into it and he rose.

Lynne Gerber: He started by talking about what it was like in the hospital.

Jim Mitulski: I was on a ventilator for several days and, uh, one of the things that happens on a ventilator is that you have a tube in your throat and you can't talk. But no one told me that, actually, that I had a ventilator, that I was on a ventilator. They just thought I knew or, I don't know, maybe they told me. I was on morphine. A lot of things happened on that, I'll tell you. So I had several days where I couldn't talk but didn't know why. And, uh, I'm very verbal, you know me, I'm a blabbermouth. So not being able to talk was really, it was maddening. And what got me through that experience was praying. And I was able to write, I wanted a rosary, so I had this sort of throwback to my Catholic childhood, but it's because you can count prayers on a rosary. And I would have these moments of thinking, I'm going to go out of my mind in the next minute because I can't talk and I don't know why, and I would say, just pray ten prayers. and see if you still feel insane at the end. And it calmed me every single time when I was able to pray that way. My mother was chatting with the nurse long distance from Michigan, and the nurse said See, they all return to the old ways. And while I was there at I was just surrounded with tape, lots of tape. They kept taping more and more. And it got, the rosary actually got taped to my chest at one point. And, uh, it started showing up on x rays. And I couldn't talk. I couldn't talk, so I couldn't tell them it was there, you know. And, uh, I thought, I could sell this photograph to the National Enquirer. I didn't come in with it. I don't know where it came from.

Lynne Gerber: And then he preached on one of his favorite stories -- the biblical story of the death of the prophet Elijah. And how Elijah's friend and student, Elisha, accompanied him through it.

Jim Mitulski: This, um, passage from, uh, Second Kings. I love, as I said, I've studied it extensively. It's a, it's a pals story. I love all the pals stories in the, in the Hebrew Scriptures. The Ruth and Naomi, the David and Jonathan, and Elijah and Elisha, pals. And, uh, if you've been following the series, you know that Elijah and Elisha went through a lot together. They had dramatic stories, many things happened to them. They were more like Lucy in Ethel Does Palestine.

Lynne Gerber: Jim had preached on this story a lot. It had becoming an AIDS scripture for him. But it looked different from this side of his HIV diagnosis.

Jim Mitulski: But there's, it was drawing to an end, um, here. And the first verse says, Now when God was about to take Elijah up to heaven, in a whirlwind, In a whirlwind. That's described in this passage. And, you know, I said I've used this story many times, I've read it many times. I realized I always read it, um, as if I were Elisha. And this time, um, these last few weeks, it just came to me. I was reading the story very differently from the Elijah perspective. I've always, and many of us have been in that caring for someone. situation, and all of a sudden, for the first time in my life, I was the one who was being cared for, and facing an uncertain time. And that really changed this whole story for me. And what happens, um, next, is that Elijah says to Elisha, Stay here for, God is sending me a little further to Bethel. Why don't you just stay here, and I'll go on alone. We've had a great time together, but you don't need to go this last little distance with me. And Elisha says, as God lives, and as you yourself live, I will never leave you. I'll never leave you. And I believe Elijah understood that he was about to die or about to go through something very difficult.

Jim Mitulski: And it's because he loved Elisha that he was saying, Oh, you don't have to do this. You really don't have to do this. And, uh, Elisha said, I can't not. And that's part of what I experienced, um, when I was in the hospital. It was kind of hard to see my friends, uh, acting panicked all the time, you know. And I wanted to say to them, you don't have to do this, but you know what, I was so grateful that they were there and that they did do this.

Jim Mitulski: And there's something about the connections we have with each other. That's where God appears. That's really where it happens. That's it. That's the theophany. That's the whirlwind. That's the still, small voice. When we're able to stick through with each other in difficult times.

Lynne Gerber: So Elijah and Elisha continue on this last journey together. Lots of people along the way expect Elisha to take an out. They don't understand why he doesn't. But Elisha's clear. He's staying with Elijah until whatever happens happens.

Lynne Gerber: Then they got to the last journey's last stop.

Jim Mitulski: Elijah says to Elisha, What do you want? Is there anything I can give you? And Elisha says, Well, I guess I do want one thing. I want a double share of your spirit. A double share, not just a little. I want to remember you. I want to feel you [00:44:00] alive with me. A double share. His love for Elijah made him greedy to want more. A double portion. And so, Elijah says to him, you've asked a really hard thing, but I'll tell you, if you're able to stick this out with me, he says literally, if you see me as I am being taken from you, You'll get what you need to go through this and to prosper.

Jim Mitulski: And I know that Elijah was sharing with Elisha a hard truth that I have seen played out here many times in our community. Um, Elijah was saying, if you can stick this out to the very end, as difficult as it is, because of your faithfulness, you will be able to transcend this afterwards. There's no judgment for Elisha if Elisha can't. Elijah gave him plenty of opportunities to not do it. And I don't, and I don't think that there's any judgment in there. Sometimes we can't do that for our friends. That happens too. [00:45:00] But when we're able to see it through, we receive a blessing like no other. Not just a double share, I think a triple or quadruple share or more.

Lynne Gerber: It wasn't about how he got it, who he got from, what he did or didn't do to get it. That was never the moral message for Jim. It was about staying with each other, even in those moments that we know will pull us apart. For as long as we can. If we can.

Jim Mitulski: What I'm learning is, we, through our connections with each other that we build over many years time, in our friendships, and in this community. We have the resources and the spirit to see through the difficult times, whatever those are. Sometimes we're Elisha, and all of us are going to be Elijah one time or another. We really will be. But it's because of our [00:46:00] relationships that we really receive what we need to get through this, whatever it is.

Lynne Gerber: And then Elijah and Elisha are pulled apart.

Jim Mitulski: These verses 11 and 12 from 2 Kings, I think are among the most beautiful in the Hebrew Scriptures. And as they still went on and talked, a chariot of fire and horses of fire separated the two of them. And Elijah went up by a whirlwind into heaven, and Elisha saw it, he saw it. And he cried out all the while, my teacher, my teacher, the chariots of Israel and its riders. And Elisha saw Elijah no more. Here it is. This is the scene, and we've been there, we'll be there again, all of us will be there at one time. But something was happening to both Elijah and Elisha at this moment. Both were transformed in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye. And Elisha got what he needed to go on and live. And he went back, and he continued his [00:47:00] life. He never forgot his friend, but he received the double portion that enabled him to continue to go and make changes in the world around him.

Lynne Gerber: Elijah went somewhere. To heaven. In a whirlwind. And the double blessing that Elisha got? It let him go on and live. To not forget. And to make changes in the world. Transformed.

Lynne Gerber: When Jim got diagnosed, in 1995, the field of AIDS treatment was changing really fast.

Justin Tanis: But this was before Protease there wasn't really, um, I guess, I guess they must have given him AZT, but there wasn't, there wasn't much combating what was the underlying cause of his illness, you know, so, um, I'd say it took a long, I mean, in some ways it's miraculous he lived.

Lynne Gerber: He was lucky to be in San Francisco.

Jim Mitulski: So I got into a trial for a drug. Compassionate use, they called it. So you have to, like, sign away all liability. But, you know, what the hell? Sure, I'll try that. I went home for a day Then I came back and did this whole aftercare thing and that's when they told me all the information about my t cells and blah, blah, blah. That's how I got into the study. I Can't remember the name of the drug, But anyway, it was like 32 pills a day.

Lynne Gerber: The cocktail -- the combination of antiviral drugs, including protease inhibitors, that would transform the course of the epidemic -- was just in reach for Jim. It saved his life. And it signaled to folks that maybe, just maybe, change was coming. After all these years and all that loss. Kevin was part of the community-based drug approval process. And he could feel it.

Kevin Fong: And so I knew what was coming down and what was pissing me off was I was losing friends. You know, I lost my best friend in 94 and I, we were, we were like eight months shy of, it was in the approval process and we were fucking eight months shy of that. And I felt like, It was my fault that I wasn't acting hard enough or pushing fast enough or maybe I was too cautious and we could have had it approved earlier. And so everybody that kind of seroconverted after 95, including Jim, it felt like, all right, I couldn't save Scott. I couldn't save Gerard. I couldn't save Tom. I couldn't save George. I couldn't save Brucie. I couldn't save, you know, you add on to that. But I can save this person. And so, um, there was a sense of both sadness, despair, and hope at the same time when he made it like almost and relief, like, thank God you didn't start serial convert three and a half years ago or two years ago, even. Um, cause I wouldn't have had hope. Um, and so it was, it was a bit like, okay, we can do this. We got this, we got this and thank God we got it and we got him.

Lynne Gerber: Next time, on When We All Get to Heaven.

Jim Mitulski: Oh, the Queer Youth Shelter was at MCC. Um, that was the most controversial thing of all. Do you know this, about this chapter? Oh my god. Gays against the homeless. That's what I call it.

CREDITS

When We all Get To Heaven is a project of Eureka Street Productions and is distributed by Slate. It was co-created and produced by me, Lynne Gerber, Siri Colom and Ariana Nedelman.

We’re so glad you’re listening and we want to be connected with you. Please take a minute and follow us on Instagram at Eureka dot Street. You can also sign up for our newsletter on our website at heavenpodcast.org.

Our story editor is Sayre Quevedo. Our sound designer is David Herman. Our first managing producer was Sarah Ventre. Our current managing producer is Krissy Clark. Tim Dillinger-Curenton is our Consulting Producer. Betsy Towner Levine is our fact checker. And our outreach coordinator is Ariana Martinez.

The music comes largely from MCC San Francisco’s archive and is performed by its members, ministers, and friends. Additional music is by Domestic BGM.

We had additional story editing support from Arwen Nicks, Allison Behringer, and Krissy Clark.

A lot of other people helped make this project possible, you can find their names on our website. You can also find pictures and links for each episode there at – heavenpodcast.org.

Our project is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, the E. Rhodes and Leona B Carpenter Foundation and some amazing individual donors. It was also made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. You can visit them at www.calhum.org.

Eureka Street Productions has 501c3 status through our fiscal sponsor FJC: A Foundation of Philanthropic Funds

And many thanks to MCC San Francisco, its members, and its clergy past and present – for all of their work and for always supporting ours.